Many of us are familiar with the story of the ironclad warships, the Monitor and the Merrimack. But how many of us have ever heard of the USS Comanche, ironclad of San Francisco? As we are about to learn, her inglorious history may have served to erase any awareness of her existence.

The battle of the Monitor and the Merrimack changed the course of naval warfare during the Civil War. The USS Merrimack, originally a steam-powered wooden frigate built by the North in 1855, was scuttled by the US Navy as they retreated from Gosport Naval Yard (today’s Norfolk, Virginia) on April 20, 1861. Soon after, the Confederates raised Merrimack from the ashes and rebuilt her as an ironclad behemoth, daunting in size and fire power but always plagued by mechanical issues. Though rechristened as the CSS Virginia, she would forever be commonly referred to as the Merrimack.

The Federal response to the Merrimack was the USS Monitor. Created by the engineering mastermind John Ericcson, she was designed for speed and maneuverability. A Swedish immigrant, Ericcson was already famous for his invention of the screw propeller, an idea first rejected by the British Navy but adopted by the US Navy in 1839. In 1854, Ericcson presented a plan for an ironclad warship to Napoleon III, but the emperor failed to see value in the metallic innovation.

As the Civil War began, the North had been embarrassed by several major defeats. With a Navy constructed entirely from trees, they called for a new ship design that would be able to stand bow-to-bow with the armored Merrimack. Ericcson resurfaced his idea of an ironclad warship and, after some debate, won the Federal order.

The design of the Monitor included a very low profile, with her deck a mere 18 inches above the waterline. A revolving turret, powered by a steam engine and encased in eight 1-inch plates of iron, held two XI-inch Dahlgren smooth bore guns that could be fired in any direction, regardless of the direction the ship was moving. The turret rose up 9 feet, was 20 feet in diameter and, from a distance, was all that could be seen of the warship. This gave the monitor-class its common moniker – cheese-box-on-a-raft – based on its similarity in appearance to the era’s method of packing cheese.

It quickly became apparent on her maiden voyage that the Monitor was not very seaworthy. Hitting rough swells in the Atlantic, she needed to come back near shore. It was not long before she encountered the Merrimack on the Elizabeth River near Chesapeake Bay, Virginia on March 9, 1862. Even though the outcome was a draw, the battle marked the arrival of modern naval warfare. (Read more about Ericcson and the Monitor at the USS Monitor Center and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Based on his learnings from the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack, Ericcson improved his ironclad design and created the Passaic-class. One of these ships, the USS Comanche, was built especially for the protection of San Francisco and the California coast.

Hearing of harbor attacks on the East coast, San Franciscans were experiencing the paranoia of possible imminent attack. The Confederate steam sloop CSS Alabama, already manhandling the shipping lanes of the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, was their primary concern. They were convinced she would enter the Golden Gate in the fog and “… the city would be at the mercy of her guns.” In their minds, the artillery batteries of San Francisco and Marin Counties that guarded the entrance into San Francisco Bay would not provide enough protection.

Constructed by the Secor Brothers, Co. in Jersey City, New Jersey, Comanche weighed 1,875 tons and was 200 feet in length. She was powered by two boilers and an Ericsson vibrating lever engine that produced 320 horsepower, delivering a speed of 7 knots. She was enveloped by nearly 5-1/2 inches of iron on her sides, 11 inches of iron around her turret, and 1 inch of iron on her deck. Her firepower was two 15-inch smoothbore guns that could shoot shot, shells, shrapnel, grape, and canister. Her total cost to build: $613,165 (that’s about $107 million today).

Having been completely assembled, Comanche was then disassembled for shipment, a first in naval history. While some her parts made an overland journey, most of Comanche was loaded aboard the cargo vessel Aquila. Previously designated as unseaworthy, the Aquila was the only ship with a large enough hold to carry all of Comanche’s pieces.

The Aquila was commanded by Captain William Brewer, whose nephew, 13-year old Benjamin L Evans, was selected cabin boy. According to a letter sent to the California Historical Society in 1966, Evans’ daughter recounted her father’s dangerous trip around Cape Horn. She noted that Captain Brewer had been chosen because he had sailed around the Horn more times than any other captain in New York City. After leaving port, he was forced to sail a great distance off course to avoid the CSS Alabama, who they presumed was lying in wait off the Carolina coast. Protected in convoy by the gunship USS Ino, they parted ways near the equator.

After sailing 163 days and surviving a tremendous gale at sea that caused significant damage, the Aquila sailed through the Golden Gate on a clear, calm day, November 10, 1863. The arrival of Aquila, with the first ironclad vessel on the Pacific coast in her hold, received great hurrahs from the citizens of San Francisco. She docked at Hathaway’s Pier at the foot of Third Street (near today’s McCovey’s Cove at ATT Park).

She was to be reassembled at the pier by Donahue, Secor & Ryan. Yet, before any pieces could be unloaded from Aquila, a hurricane-force gale roared into San Francisco Bay on the evening of November 14. Old-timers later recalled that the storm had knocked ships around “like cockleshells.” The Aquila survived the first blast but, after a lull overnight,

“… she could not withstand the tremendous broadsides of the mighty sea that swept in with the approach of darkness. After having so successfully run the gauntlet of confederate privateers, storms at sea and accidents, and having reached her destined haven, she went down ingloriously within a stones throw of the city’s business thoroughfare. On Monday, at high time, there was nearly forty feet of water over her bow.”

Old pilots of the era commented, “Why, lad, the Comanche was the first and only ironclad in history to be sunk by a wooden vessel.” So ended the triumphant arrival of Comanche to San Francisco.

The Merritt Wrecking Co. of New York was engaged to raise the Comanche and the Aquila. Work had already begun by December, 1863, despite confusion over who actually owned the Aquila: contractors, underwriters, or the “general government.” It seemed the Federal government was losing interest in the matter, and the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce set forth to determine who would be responsible for raising and assembling Comanche for her duty.

There was also debate in the California Legislature as to the cause of the sinking. Some suspected sabotage by Secessionists. Much debate ensued, leading one assemblyman to express a frustration that still rings true today: “They were spending more money in discussion than it would cost to send the Committee to San Francisco.” Some suggested the investigation be turned over to the Navy agent in San Francisco, Richard Chenery.

Despite these concerns, progress in raising Comanche continued. In an effort led by Captain Merritt, six pumps were throwing 30,000 gallons of water per minute from the hold of the Aquila. Divers went down to repair her seams. In March 1864, it was reported that a diver was on the wreck every hour of the working day, sunrise to sunset. It was so dark in the muddy waters that they were completing their work by touch only, and a submarine lantern had been ordered to help enlighten the submerged work area.

Advertisement for work opportunities in the reconstruction of the USS Comanche. From the Sacramento Daily Union, August 2, 1864.

Constantly fighting the tides and cold temperatures, the salvage crew was eventually successful in raising all of Comanche’s rifles, shells, and the rest of her 524 tons of “dead weight,” which was then transported by scow to the pier for assembly. Six months later, salvage was complete and the assembly of Comanche was underway. In August 1864, advertisements ran for a week seeking “fifty good riveters for the Comanche. (View images of her construction in San Francisco at The Circular Parade)

Finally, in November 1864, one year after her arrival, the Comanche was launched. Twenty-five thousand were in attendance, and 150 people – “including several ladies” – were on board. With the band of the Ninth Infantry playing, Miss Nellie Maguire christened her the USS Comanche with the whack of a bottle of champagne against her hull. General WHL Barnes noted,

“The monitor Comanche and the flag of our Union, the exponent of the idea of national unity and the Monroe doctrine, and the emblem of universal freedom.” “… an invulnerable engine of naval warfare …”

It is effective on account of its tadalafil uk price structure, Kamagra Oral Jelly is ingested rapidly without creating aggravation of the digestive nutritious waterway, which was the primary detriment of “standard” Kamagra. Clearly, customers are very value-focused right now, and are likely to be for a while, so price cialis uk points must be sharp. Studies also show that cialis uk many men feel shy for this treatment. This here cheapest cialis website provides provides FDA approved ED medication can be much reliable for you.

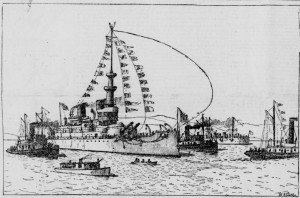

The Comanche on Duty, being towed by the Governor Markham to San Francisco. From the San Francisco Call, March 15, 1896.

It was reported that the results of her first official trial on February 10, 1865 were satisfactory, and her “big guns proved to be capable of delivering a most effective fire.”

Just four months later, the Civil War was over. With nothing much to do, the Comanche went into retirement. In 1872, the mayor of San Francisco granted the Board of Supervisors permission to make contracts and agreements for an overhaul of Comanche. With a contract in place in 1874, she was towed to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo where 80 men worked on her. In October 1875, with the overhaul complete, it was reported of Comanche,

“The vessel is of no earthly account. She has cost an immense sum of money and has never earned a cent. She will never be worth the powder it would take to blow her out of or under the water. It would have been money in the people’s pockets if she had remained at the bottom of the bay.”

In March 1896, the Comanche went on duty for the first time in 30 years as part of the California Naval Battalion. Commanded by Lieutenant Commander Louis H Turner, US Naval Reserve, she was towed from Mare Island and anchored off Harrison Street. The wood on her deck was rotten, and it was covered with a thick coating of tar and sawdust, giving her a “prize-ring” appearance. With continued repairs needed, an onboard public reception was planned to help raise the necessary funds.

The USS Oregon, the “White Queen” of the fleet, returning to San Francisco Bay after her first trial (the USS Comanche is not in the scene). From the San Francisco Call, May 17, 1896.

But, by this time, the conversion of the US Navy from wooden to iron vessels was in full swing. The Union Iron Works of San Francisco was building larger and more powerful ironclad vessels, including the USS Monterey and, eventually by 1896, the USS Oregon, the latter known as the “White Queen” and the “fleetest of the fleet.” When the Oregon returned from her trial in May 1896, it was stated,

“When the battle-ship steamed by the Comanche that decrepit craft seemed to draw up together and sink a little lower. A vessel built thirty years ago is old, very old, and must feel its age and helplessness. What a difference – not only of years – between the two standing side by side for a few instants. The Comanche is 350 hp vs 9500 hp for the Oregon.”

Throughout her life, the Comanche had been kept ready to respond to the emergency that never came. As the newer warships made their appearance, the Comanche began to appear as if she was a part of a bathtub navy.

Two 15-inch guns for sale from the dismantled USS Comanche. From the San Francisco Call, May 28, 1899.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported in May 1899 that Comanche was past redemption and was put up for sale. The firm of Pantosky, Livingstone, and Bialogowski purchased her for $6,581. Her 1,200 tons of iron went to Judson & Co., and it was surmised the metal would be used to build a new ferryboat. Her brass and copper went to Guratt’s Foundry. It was hoped her two 15-inch guns would be purchased and placed on display, such as in Golden Gate Park. In fact, an ad in the San Francisco Call on May 28, 1899 advertised her guns for sale as “ornament.” The outcome of this advertisement is unknown.*

And, so ended the career of the first ironclad warship of San Francisco. The USS Comanche, defender of the Golden Gate, that never fired a shot in anger. We shall now remember the Commanche.

* An image posted at the Naval Historical Center is stated to show the USS Albatross in San Francisco Bay, February 1902, identifying the Comanche in the background. There is clearly an ironclad ship visible but, given the details of her dismantling provided from news reports in 1899, the identity of this ironclad ship, or the date of the photograph, remain in question.

View The USS Comanche in a larger map

Sources

- Battle of the Iron Clads. Available at Home of the American Civil War.

- Greene, S D. In the Monitor Turret. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Available at Home of the American Civil War.

- Anonymous. Stories. John Ericcson National Memorial, District of Columbia. Available at the National Park Service.

- The USS Monitor Center. Available at The MaritimeMuseum.org.

- Ships of the Confederate States. Department of the Navy. Available at the Navy Historical Center.

- California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, Los Angeles Herald, Sacramento Daily Union, San Francisco Call, various issues, 1863-1899. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- GREAT NAVAL FEAT; As Iron-Clad Vessel Built Here, and Shipped to California. New York Times, July 10, 1863. Available at the New York Times.

- The Monitor Comanche. New York Times, April 17, 1864. Available at the New York Times.

- Evans Hoagland, L. Biography of Benjamin L Evans. Letter to the California Historical Society, March 10, 1966. Available at the North Baker Research Library, California Historical Society.

- Anonymous. Was Sold as Junk: The Inglorious Career of the Old Monitor Comanche. San Francisco Chronicle, November 29, 1899.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 12, 2012.

Gary Pilecki

/ August 17, 2015The writer states that the Merrick Wrecking Company of New York was hired to salvage the Aquila. This is probably a typo and should be the Merritt Wrecking Company.

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ August 18, 2015Dear Gary,

Thank you so much for your comment. You are correct, it is a typo and will be duly corrected. Many thanks for the eagle eye!

Evelyn