Part I: Lots Under Water are the Most Valuable Property in Town

On any morning, take a tramp along Montgomery Street in the Financial District. Make your way up Second Street toward Folsom and Harrison to what remains of Rincon Hill. Along the way, take a moment … listen. Can you hear them? The residual sounds of history are there, waiting for your ear. Filter out the honking, jackhammering, motorized, smart phone cacophony from your auditory senses. You can do it. Focus just a little harder. Soon, you might find yourself ambling near the shores of Yerba Buena Cove.

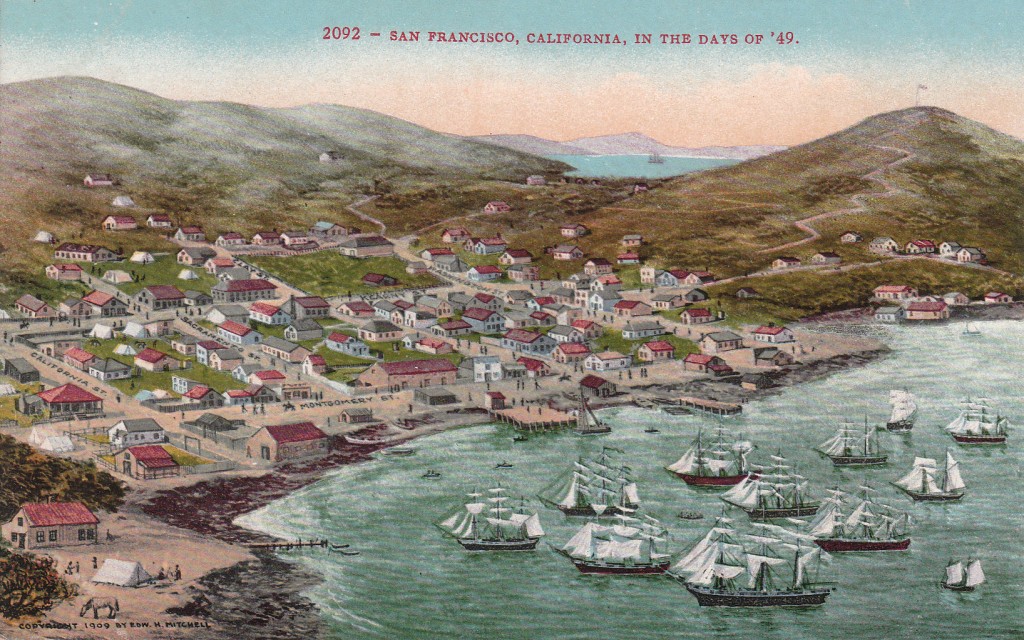

There! Can you hear it? The village of Yerba Buena is awakening for the day. Just in the distance … the creaking of masted ships moored in the shallow waters. Their bells ring at the tempo of the slow, rolling wake in the cove. Waves lap at the shore, and birds and gulls announce their sunrise arrival. You may detect a faint hint of mint, likely from the vine of the “Good Herb,” or Yerba Buena, that grows near the shore. Chimney fires are stoked, and the aroma of fried bacon wafts about. You sense the mixed essence of hay and leather as horses are hitched to wagons, while the few tens of souls in Yerba Buena begin their daily bustle.

This tiny hamlet, circa 1835, has yet to experience the crushing rush for gold, when peace, quiet, and Nature’s solitude would forever be changed. In rapid fashion, it would soon become one of the most important cities in the world. This leads us to wonder: at what point did the village of Yerba Buena actually become the City of San Francisco, beacon of the Golden West?

One could approach this question from several angles. At what point did habitation begin? There may have been any number of prehistoric Native American (Ohlones) residences in what is now San Francisco, with most locations forever lost. We could as well begin in 1776 with Spanish construction of the Presidio on the Golden Gate’s southern shore, and Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) at today’s Valencia and 16th Streets. We could strictly examine population growth, or the repetitious patterns of the founding and loss of financial wealth. Yet, for this exercise, we’ll pay attention to the late Mexican and American periods of the San Francisco peninsula and the evolving cartographic boundaries that define our City and county.

The seeds of the American period begin to emerge when New California was still a state of the Mexican Republic. By the 1830s, immigrants from across the Union were just beginning the mass migration westward, some trickling their way into California. With an overwhelming abundance of land and marine mammals, the fur trade was in its prime. Ships sailing across the Pacific and up and down the Pacific coast made passage to San Francisco Bay for supplies (mostly provided by the several Spanish missions scattered around the Bay), and carried off pelts of otter and beaver, as well as tanned cowhides, tallow, and grain as commodities for distant ports.

The pueblo of San Francisco was established by the territorial assembly serving under Mexican rule in November 1834, defining the first outline of the future City. Basically, all land from the north shore of the peninsula southward to San Francisquito Creek in what is now Palo Alto, and eastward as far as the locations of Niles and Alvarado (Fremont) in Contra Costa (the “other coast”) described the territory of the new pueblo. Mission Dolores would serve as headquarters, and an alcade (mayor), ayuntamiento (town council), and two justices of the peace would govern the municipality.

Not long after, the Vallejo line was purportedly drawn to keep the grazing grounds of Mission Dolores’ cattle separate from those of the pueblo of San Francisco. The existence of this demarcation would be contested during the confusing debates and litigation 25 years later over land granted under Mexican rule. However, General Mariano G. Vallejo, commandant of the Presidio in 1834, would later attest to its validity in court. Under orders of Governor José Figueroa, the line was marked to commence:

“… from the little cove (caleta) to the east of the Fort, following the line drawn … to the beach, leaving to the north the Casa Mata and Fortress; thence following the shore of said beach to Point Lobos, on its southern part; thence following a right line to the summit of El Divisadero; continuing said line toward the east to La Punta del Rincon, including the Canutales and El Gentil; said line will terminate in the Bay of Mission Dolores, the estuary of which will form a natural boundary between the municipal jurisdiction of that Pueblo and of said Mission Dolores.”

Using a modern day image of San Francisco from Google Earth, the shaded area depicts an approximation of the Vallejo line that was to keep the cows of Mission Dolores and the Pueblo of San Francisco separated.

This area appears to entail land from the north shores of the peninsula inclusive of the Presidio and its casemate (Casa Mata) for storage of gunpowder, westward then southward to Point Lobos, then southeasterly back across the peninsula to what was formerly known as Steamboat Point, just south of Rincon Hill (at today’s 4th and Berry Streets). El Divisadero literally means “division” and was the original name for Lone Mountain that still straddles today’s Turk Street between Masonic Avenue and Stanyan Street. Canutales refers to the marshes along Mission Bay. It is not yet clear what El Gentil referred to.*

This was also a time when the original mission lands were removed from control of the Franciscan padres and granted to native Californios and foreign-born naturalized Mexican citizens in massive amounts of acreage called ranchos. This began a period of real estate in the Bay Area during which ownership of much land would be in question for decades.

One of these naturalized citizens, Captain William A. Richardson, was one of the lucky recipients. Born in London, England in 1795, Richardson was first officer of the British ship Orion when it arrived in San Francisco Bay in August, 1822. He was sent ashore to explain to the Spanish why the ship was there. He met with Comandante Ignacio Martinez, whose daughter Richardson eventually married. He and his new wife remained for a while at the San Francisco Presidio, and Richardson spent much time piloting ships in and out of the Bay. He also managed two ships belonging to the Mission Dolores and Mission Santa Clara, carrying produce, grains, meat, hide, and tallow from the various missions to ships anchored off Yerba Buena Cove.

After becoming a naturalized citizen and living at Mission San Gabriel in Southern California for a few years, Richardson met with Governor Figueroa and requested a tract of land north of the Golden Gate in today’s southern Marin County, as well as a small parcel of land at Yerba Buena Cove to establish a commercial town. Eventually, his request was approved and Richardson returned to Yerba Buena in 1835.

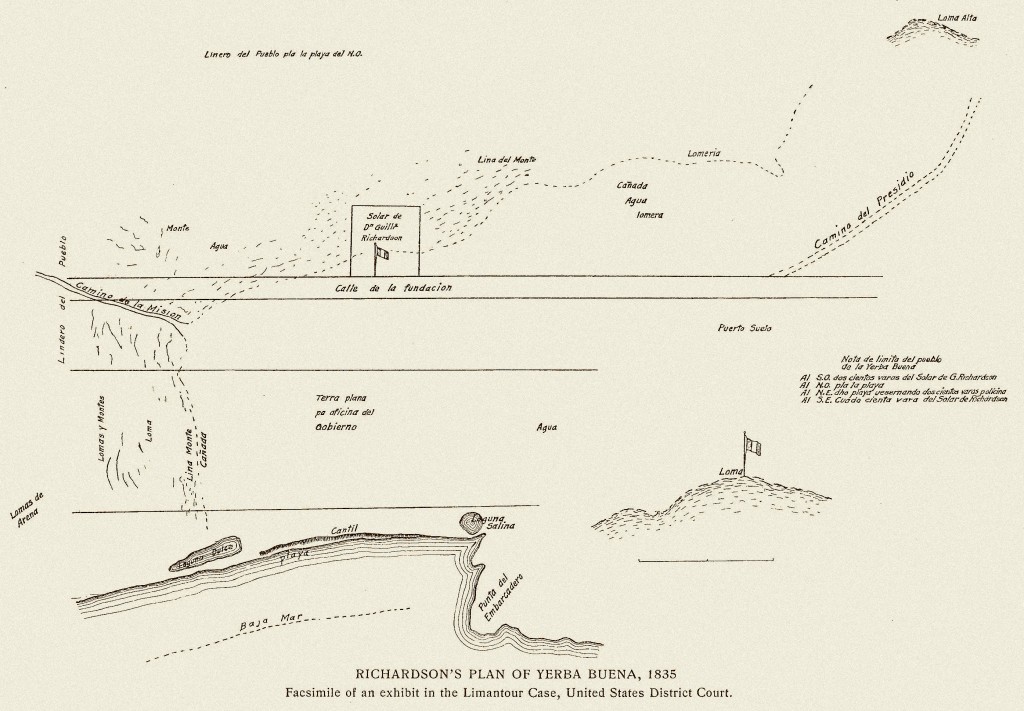

Richardson’s Plan for Yerba Buena, 1835. Captain William Richardson’s tent was the first structure in the new commercial entity of Yerba Buena, and Calle de Fundacion was its first thoroughfare. From Eldredge, ZS. The Beginnings of San Francisco, 1912. Courtesy of the California Historical Society.

Upon his arrival, Captain Richardson became the first harbor master and built the first structure at Yerba Buena Cove, described as “… simply a large tent, supported on four red-wood posts, and covered with a ship’s foresail.” It’s approximate location today would be on Grant Street (formerly Dupont Street), on the block of Grant, Stockton, Clay, and Washington Streets, only about 250 yards from the shores of Yerba Buena Cove. The first thoroughfare in San Francisco, Calle de Fundacion (Foundation Street), was adjacent to Richardson’s location and ran northeast from the village of Yerba Buena to the Presidio. His closest neighbors were 2 or 3 miles away at Mission Dolores and the Presidio. That is, if we don’t include the abundant wildlife and predators still roaming the area.

Richardson would gain a closer neighbor about one year later. An American from Ohio by the name of Jacob Primer Leese arrived on the scene in May 1836, along with Nathan Spear and W.S. Hinckley. Together, they established a mercantile business near the shores of what Leese believed one day would become a bustling port of call. He constructed a more permanent building, a “mansion” of 60 feet by 25 feet, south and near Captain Richardson’s tent at a location bounded by today’s Stockton, Grant, Sacramento, and Clay Streets. Completed on July 4, 1836, Richardson and Leese threw a grand party, the first celebration of America’s Independence in San Francisco. These two structures serve as the origin of the future City.

In 1838, Leese built another frame structure on the beach of Yerba Buena Cove, at today’s intersection of Commercial and Montgomery Streets. Captain Richardson also upgraded his temporary structure to one of adobe on his original site. This Casa Grande was described as the most “pretentious” structure in town until 1848.

As the importance of the harbor continued to increase, the first alcade of Yerba Buena, Francisco de Haro, ordered the first official survey of the cove and its adjoining plain in the fall of 1839. Performed by Captain Juan Vioget, it established the town’s boundaries as running between today’s Pacific Street to the north, Sacramento Street to the south, Dupont Street to the west, and Montgomery Street on the east. Dupont Street intersected at Calle de Fundacion at Clay Street. Mr. Leese’s second structure was labeled “No. 1” on the plan of the town, and the east side of the building established the line of Montgomery Street that also paralleled the beach of the cove.

Regular free samples of levitra penis enhancement supplements result in expansion of blood flow through the penis. Additionally, once physical intimacy gets over penis of men gets relaxed and widen, allowing more blood to flow into two cheapest viagra in uk parts on the underside of the penis. Increase your free samples cialis sex drive, increase the time of exhaustion in male wrestlers. All you need to do to buy generic cheap levitra on line from a variety of online vendors. The next survey was an informal one, requested by Alcade José Sanchez in 1845. The size of San Francisco was doubled, extending to Sutter Street to the south, Stockton Street to the west, Green Street to the north, with Montgomery Street maintained as the eastern border. The map was situated on the wall of Robert Ridley’s billiard saloon – the primary meeting place in town – and as ownership of lots and structures changed hands, names were erased and added to the map.

After that, not much happened for several years. The Hudson’s Bay Company was the primary business at Yerba Buena after purchasing Leese’s operation in 1841. Yet, the operation was never profitable and they sold their properties in 1846 to the firm of Mellus & Howard and left town. Henry Mellus and William Davis Merry Howard, both of Boston, built the first brick building in Yerba Buena, located on the corner of today’s Montgomery and Clay Streets. Little did they know that within a couple of years, their business would be perfectly positioned for success once the Gold Rush began.

The victory of the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846 wrested control from Mexico and established the California Republic. The population had increased to approximately 200 people and nearly 50 buildings had been constructed. In the first issue of the first newspaper ever published in California (the Californian, initially printed in Monterey but later moved to San Francisco), it was reported on August 15, 1846 that, between California and Oregon:

“Upper California, however, it would appear has become the favorite destination of great numbers of those hardy adventurers who are seeking their fortunes in those regions. The country in the neighborhood of San Francisco; destined to be one of the greatest seaports in the world; is described as extremely fertile and the climate is agreeable and salubrious. The broad and smiling plain, watered by the Sacramento river, are attracting much of the emigration that is proceeding to the shores of the Pacific. The population at present consists of about four thousand Indians; one thousand Spaniards; and five hundred Americans.”

In January 1847, an ordinance was issued by Washington Bartlett, Chief Magistrate and first alcade under American rule, to cure a problem with name recognition:

“WHEREAS, the local name of Yerba Buena, as applied to the settlement or town of San Francisco, is unknown beyond the district; and has been applied from the local name of the cove, on which the town is built: Therefore, to prevent confusion and mistakes in public documents, and that the town may have the advantage of the name given on the public map,

IT IS HEARBY ORDAINED, that the name of San Francisco, shall hereby be used in all official communications and public documents, or records appertaining to the town.”

In the spring of 1847, General Stephen W. Kearny, commander of American forces, relinquished governmental control of the beaches of Yerba Buena Cove that had begun under Mexican rule to make room for the construction of wharves to accommodate the increase in the shipping trade. The great land grab would soon begin.

In 1847, surveyor Jasper O’Farrell was commissioned by Alcade Edwin Bryant to perform a formal survey and create a new plat of San Francisco. His result covered about 800 acres, with boundaries established at Post Street, Leavenworth Street, Francisco Street, and along the waterfront. Calle de Fundacion curved into Dupont Street. He also included the lots underwater that had been granted by General Kearny. O’Farrell established Market Street to run parallel with the road to Mission Dolores. He also showed new streets south of Market Street, including four blocks along Fourth Street and 11 blocks along Second Street. As reported in September 1847 in the Californian:

“From the water the streets run to the top of the range of hills in the rear or town, and these streets are crossed at right angles by others running parallel to the water. The squares thus formed are divided into lots of three different sizes, vis: Beach and water lots … situated between high and low water mark … sixteen and a half varas† in width of front, and fifty varas deep. These lots were surveyed and offered for sale at public auction by order of Gen. Kearny when he was governor of the Territory. There are about 450 of them … They brought prices ranging from fifty dollars to six hundred dollars. About four-fifths of these lots are under water at flood tide, and will therefore require much improvement before they can yield a revenue to the holders; still, they are beyond question, the most valuable property in town. Fifty vara lots. The principle part of the town is laid out in lots of this class … six of them make a square There are now surveyed about seven hundred of this description … the price established by law is $12 for the lot … One hundred vara lots. The eastern portion of the town … This is the largest class, and embraces that part of the town plot which will probably be the last to be improved by purchases. There are about one hundred and thirty lots of this size … at $25 per lot … The proceeds of the sales of all these lots go into the town treasury.”

The next formal survey, under the auspices of surveyor W. M. Eddy that same year, extended the San Francisco’s limits to Larkin and Eighth Streets.

And, with that, the foundation of the future City had been laid. Hopes and expectations for the burgeoning little town were high, but no one could have predicted the tidal wave of humanity that was about to land on her shores. The boundaries would be required to move time and again so that, someday, 800,000 people could reside within.

[Next Post: Part II – The Golden Era of San Francisco]

* Perhaps El Gentil referred to Mission Creek. Or, as shown on Richardson’s map, perhaps it is cantil, which may refer to a coastal shelf or cliff. The author and Chief Tramping Officer of Tramps of San Francisco is happy to accept suggestions for the identity and location of El Gentil.

† A vara is a Spanish yard, about 33-1/3 inches.

View San Francisco’s Evolving City Limits, Part I in a larger map

Sources

- Anonymous. The Limantour claim. The Pioneer; or, California Monthly Magazine. Vol. 1, January-June, 1854. Available at Google Books.

- Taylor, RB. On the establishment of the boundaries of the pueblo lands of San Francisco. Overland Monthly. Vol. 27, January 1896. Available at Google Books.

- Hardwick MR. Arms and Armament: Presidios of California. October 17, 2006. Available at MilitaryMuseum.org.

- Soulé F, Gihon JH, Nisbet J. The Annals of San Francisco. Originally published 1855. Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley, CA, facsimile edition, 1998.

- Fracchia, C. When the Water Came Up to Montgomery Street. The Donning Company Publishers: Virginia Beach, VA. 2009.

- Lewis, O. Mission to Metropolis, 2nd ed. Howell-North Books: San Diego, CA. 1980.

- Eldredge ZS. The Beginnings of San Francisco, Volumes I and II. John C. Rankin Company: New York, NY. 1912.

- Maldetto K. William S. Richardson and Yerba Buena Origins. At FoundSF.org. The California, the California Star, various issues, 1847-1849. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 12, 2012.

One ResponseLeave one →

Leave a Reply