Part III: The Land of Giants

”There is not much great timber, nor indeed wood of any kind, …”

— The Annals of San Francisco, 1855

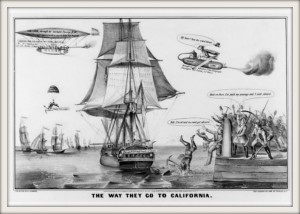

By 1850, the most significant “trees” in San Francisco could be viewed among the “forests” of the felled kind, mainly in the form of ships’ masts and other structures. By then, over 600 ships had been abandoned in Yerba Buena Cove as captains and sailors alike hurled themselves overboard, abandoning ship in a mad dash for the Sierra gold diggings.

As discovered in Parts I and II of this series, early residents had already recognized the northern San Francisco peninsula as the “the most barren part of the district.” Yet, this lack of immediately available timber would fail to derail the founding of one of the world’s great cities, soon to be rapidly entrenched with “excitement-craving, money-seeking, luxurious-living, reckless, heaven-earth-and-hell-daring” citizens – a description that some may believe applicable to gentrification debates in these modern times.

The paucity of forests in the immediate vicinity provided the greatest of challenges to early residents, beginning with the earliest European settlement. Padre Pedro Font of the 1776 de Anza expedition, standing high on the cantil blanco (the white cliffs of today’s Fort Point), commented on the beauty of the area and noted just one omission: “Only timber was lacking, as there was no tree on those heights; but not far away were live oaks and other trees.”

In another 80 years, standing on Telegraph Hill and spying across the water through atmosphere unstained by particulates, an abundance of trees along the ridges of the Coast Range surrounding the Bay were clearly visible, as noted in the Annals of San Francisco:

“Farther out was the high lying island of Yerba Buena, green to the summit. Beyond it lay the mountains of Contra Costa, likewise arrayed in verdant robes, on the very tops of which flourished groups of huge redwood trees; while far in the distance towered the gray head of Monte Diablo.”

Various types of oak, pine, maple, alder and other species would soon be harvested around the Bay Area. But, the most desirable of all, California’s coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), prized for its size, beauty, and resilience, will be the focus of this and the next two posts. A magnificent species found only in California and a tiny sliver of Oregon, the coast redwood would provide more than a mammoth share to the infrastructure of the burgeoning populace of San Francisco, and in the process be nearly sawed and milled to virginal extinction.

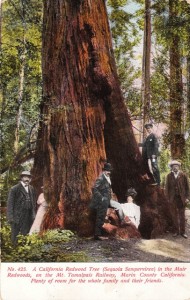

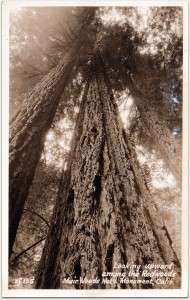

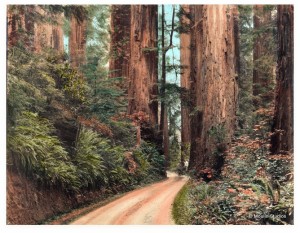

“There are great numbers of this tree here, of all sizes of thickness, most of them exceedingly high and straight like so many candles.” — Padre Juan Crespi, 1769. Postcard from the collection of Evelyn Rose.

During the Portolá expedition of 1769, only weeks before the team discovered San Francisco Bay, Padre Juan Crespí recorded the first description of these giant trees of the New World in his journal. While traversing along the Pajaro River, near today’s Watsonville:

“For besides the many good-sized cottonwoods on the river, there begins here a large mountain range covered with a tree very like the pine in its leaf, save that it is not over two fingers long. The heartwood is red, very handsome wood, handsomer than cedar. No one knew what kind of wood it might be; it may be spruce, we cannot tell. Many said savin [Trampers’ note: a shrub juniper (Juniper sabina), native to Europe and western parts of Asia], and savin ’twas called, though I have never seen them red. There are great numbers of this tree here, of all sizes of thickness, most of them exceedingly high and straight like so many candles. What a pleasure to see this blessing of timber.”

“… In this region, there is great abundance of these trees and because none of the expedition recognizes them, they are named redwood for their color.”

Miguel Costansó, an engineer of the same expedition, noted,

“We set out from the Laguna del Corral [near today’s Santa Cruz] … We directed our course to the north-northwest, without withdrawing far from the coast, from which we were separated by some high hills thickly covered with trees that some said were savins. They were the largest, highest, and straightest trees that we had seen up to that time; some of them were four or five yards in diameter …”

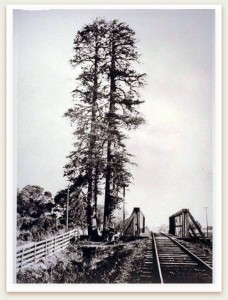

Seven years later, Padre Font would observe twin redwoods on the banks of San Francisquito Creek in today’s Palo Alto, reportedly visible from distant points around the Bay. He measured …

“… its dimensions by means of the graphometer which he had loaned [sic] from Fr. Palóu at Mission San Carlos. While savage Indians stood gaping at his proceedings, Fr. Font calculated that the solitary redwood tree was about fifty varas* in height (140 feet), and the trunk at the base was five and one-half varas in circumference (15 1/2 feet).”

This tree, known as El Palo Alto (literally, The Tall Tree), is the namesake for the City

This 1875 photograph shows the twin-trunk of el Palo Alto adjacent to the single-track railroad bridge, looking from the San Mateo County side of San Francisquito Creek. Image 053-005. From the Guy Miller Archives, Palo Alto Historical Association.

of Palo Alto. Designated as California Historical Landmark No. 2, it is California’s first living landmark. In 1861, ground-breaking for the San Francisco and San Jose Railroad was held adjacent to the tree. For over 150 years, El Palo Alto has endured severe physical stress as trains continue to lumber by within a few feet of its base.

Known to be 1054 years old, it is smaller now than it was in 1776, measuring 110 feet in height and over 8 feet in diameter. Its reduced girth is due to the loss of its twin in an 1887 flood; its smaller height the result of preservation efforts in 1977 and 1999 that twice removed the dead top, unable to tolerate decades of exposure to coal-based soot spewed by passing locomotives. A gradual reduction in the Silicon Valley water table during the years when agriculture reigned supreme may have also played a role. Today, El Palo Alto is declared to be healthier than it was a century ago, and projections are it may be able to survive at least another 300 years.

Photographer Gabriel Moulin (1872-1945), known as the “Redwoods Photographer,” captured images of coast redwood forests up and down Northern California. Moulin became the official photographer for the Bohemian Club beginning in 1898. The location and date of this image is not yet identified. Used with permission from Jean Moulin, Moulin Studios. From the collection of Evelyn Rose.

Several features of El Palo Alto hint at some of the special characteristics of the coast redwood that collectively define the redwood mystique, making it highly valued by both loggers and preservationists. I’ve volunteered as a docent at Muir Woods National Monument for over 11 years, and with each visit the trees of Redwood Canyon evoke new wonderment and reflection. Ernest Peixotto, artist, illustrator, and bohemian, described the old-growth coast redwood forest owned by the Bohemian Club in 1910:

“On a bend of the Russian River about eighty miles to the north of San Francisco there stands a forest of redwood trees, never touched by the woodman’s ax, a grove whose mighty tree trunks, massive as the clustered columns of a Gothic cathedral, lift their heads skyward in stately and imposing order, devoid of branches to a great height. In distant perspectives of these dim-lit forest aisles, the boughs of far-off treetops interlace in flowing traceries, framing peeps of sky into mullioned windows of strange and beautiful design. Sunbeams filter through the shimmering leaves and play in brilliant spots upon the ground, but the light falls sparingly, as in the rich gloom of some church interior.

“Did you ever rest in the nave of a cathedral? Did you ever follow the lift of its mighty piers, the arch of its soaring vaults, the far perspectives of aisle and transept and chapel, the broad sweep of the pavement? So in these forest aisles. The shafts, nerved with bark, the interlacing feathery boughs, the colored sky windows, the floor carpeted with pine needles – droppings of ages, softer underfoot than the priceless weaves of the ‘Savonnerie’ [French tapestry]. No sound breaks the eternal solitude except at times the tap of a woodpecker, the chirp of a squirrel, or the wind sighing through the pine boughs high upon the summit of the trees, radiant in the sunshine.”

Coast Redwood 101

As we’ll see in subsequent posts, many features of the coast redwood created astonishment and perplexity among early residents of San Francisco, sometimes with humorous results. Therefore, a review of these unique characteristics is in order.

Walk within any stand of old growth, virgin (meaning never logged) California coast redwood and you will sense a forest primeval. This fir (not a pine as described by Peixotto) is the tallest species of tree or any other living thing on our planet. Its gargantuan proportions mirror that of some prehistoric reptiles.

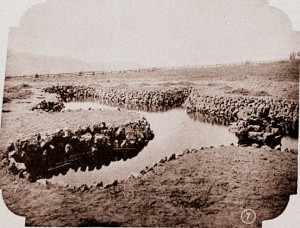

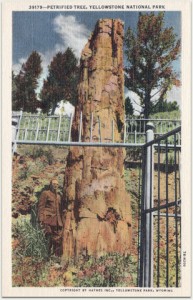

This petrified redwood is a remnant of the wide geographic distribution during the time of the dinosaurs. This tree still stands today in Yellowstone National Park near Tower Junction. Postcard from the collection of Evelyn Rose.

In fact, ancestors of the coast redwood emerged during the time of the dinosaurs in the Cretaceous period, 165 to 135 million years ago. By about 65 million years ago, redwoods were thriving in a mild and humid climate, extending their distribution throughout the northern hemisphere. Yet, about 3 million years ago, through the action of plate tectonics, uplift of mountains, and decline of temperate conditions, prehistoric redwood eventually became extinct in the eastern United States, Greenland, Europe, and the majority of Asia. Today, fossil evidence of redwood can be found as close as Calistoga in Napa County (The Petrified Forest), and in such far-ranging locations as Nevada, Arizona, Wyoming, Spain, and near the North Pole.

After its initial description by Crespí, the first botanist to view the coast redwood was Thaddeus Haenke of the Malaspina Expedition (1791). After making landfall at Monterey Bay, Haenke returned samples and seeds to Spain. As late 20 years ago, it was reported a redwood tree from one of these seeds was still growing somewhere in Spain. Scottish surgeon and botanist Archibald Menzies of the Vancouver Expedition (1792) would also return samples from Santa Cruz to England.

Neither Haenke nor Menzies would attempt to scientifically classify the redwood. That would be left to Aylmer Bourke Lambert, who over a half century later would use Menzies’ samples stored at the British Museum (Natural History) in London. He assigned coast redwood to the Taxodiaceae family, a type of cypress. Many botanists now classify coast redwood as a member of the Cupressaceae cypress family, which has merged with the Taxodiaceae because of many shared characteristics.

Today’s scientific name for coast redwood, Sequoia sempervirens, was adopted by Austrian Stephen Endlicher in 1847. He died before he could properly explain the meaning of Sequoia. However, it is generally believed he was honoring Chief Sequoyah of the Cherokee Nation. In 1821, Sequoyah developed a phonetic alphabet that gave his people the ability to not only speak but also read and write in their native tongue, an accomplishment that garnered worldwide praise. As a conifer (or, cone-bearing tree), coast redwood is not deciduous but rather sempervirens – Latin for “always green” throughout the year.

Two other types of Sequoia exist today. The giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) is not as tall as its coastal cousin but in bulk is one of the largest living things on Earth (Trampers’ note: a fungal mat of the honey mushroom in Oregon is the largest living thing in mass, spreading over 2200 acres). Found only in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California and as heavily logged in the mid- to late-19th century as the coast redwood, shipment of giant sequoia timber products from the mountains to San Francisco was considered economically unfeasible with the technology available at the time.

The other type of redwood, the dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), is confined to only three provinces in central China. Unlike the coast redwood and giant sequoia, the dawn redwood is deciduous and will lose its leaves (needles) in the winter. Once thought to have been extinct for over 20 million years, living specimens were found by a Chinese botanist in 1944. With fewer than 5,400 old growth trees remaining amidst continued expansion of industry and agriculture in its native region, the future of the dawn redwood seems uncertain.

As does the future of the coast redwood and giant sequoia. Neither is listed as an endangered, threatened, or candidate species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, though virgin forests of coast redwood support nine different species of plants and animals federally designated as endangered. However, the Red List of the agency adopted by the European Union, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) does classify all three redwoods as endangered.

An estimated 10 million acres of virgin coast redwood existed along the northern California coast before Euro-American settlement. According to the IUCN, at the turn of the 21st century, coast redwood comprised 843,000 acres of woodland, of which 643,000 acres (76%) was for commercial purposes. Stands of redwood on these lands are considered second- or third-growth, meaning the forest has been logged one or more times. Many heavy-handed methods used to harvest redwood can obliterate nearly all vestiges of the virgin forest. The old-growth survivors of today (about 200,000 acres) only represent about 2% of the original 10 million prehistoric acres. Fortunately, most of these virgin forests are now under California state or federal protection.

It may take around 250 years for a coast redwood to reach its maximum height, with young redwoods growing as much as one foot annually. Today’s top monarch of coast redwood, at a hair-shy of 380 feet tall (equivalent to a 35-story building), is Hyperion, towering over an unidentified location near Eureka in Redwood National Park. Helios, Stratosphere, Icarus, Paradox, Lauralyn, and Orion, are seven other coast redwoods that rise to within 10 feet of this giant. Over 600 trees in excess of 340 feet in height are known to exist in far Northern California between Montgomery Woods State Natural Preserve near Mendocino, up through Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park near the Oregon border.

Moving southward, as accumulation of annual moisture gradually declines, coast redwood generally reaches to lesser heights but are still nothing to scoff at. For example, a tree at Muir Woods National Monument towers 258 feet above Redwood Canyon. If placed on the roadway of the Golden Gate Bridge, it would rise another 12 feet above either of the bridge’s main towers.

The Mediterranean climate of Northern California, settling in place about 8 million years ago, replicates the climatic conditions ancient redwoods required: mild variation in annual temperature, rainy winters, and rainless but foggy summers. Over the past 3 million years, the ebb and flow of glaciers with alternating warming and cooling of climate served to isolate the distribution of California coast redwood to only the northern California coast.

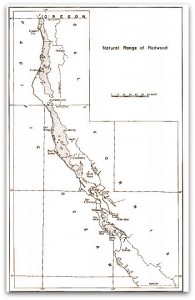

From the Santa Lucia Range in southern Monterey County extending 450 miles northward to Oregon at a tributary of the Chetco River named Redwood Creek, the range extends no more than 15 miles beyond the California state line. Coast redwood, on average, can reach 20 to 25 miles inland, though lesser or greater distances may occur depending on the reach of the cool, foggy marine layer. For example, a native stand of redwood in southern Napa County is 42 miles from the Pacific shore.

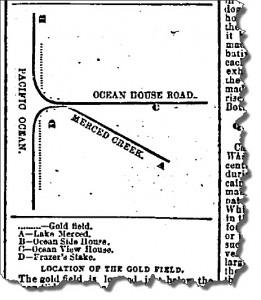

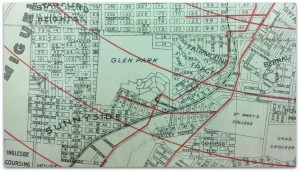

This map details the native range of California’s coast redwood. Moving from the Oregon border south through Sonoma County, distribution is solid. Yet, south of Sonoma County, where average annual precipitation begins to decline, distribution becomes more irregular. From Roy DF. Silvical Characteristics of the Coast Redwood. 1966. Available at the U.S. Forest Service.

A solid distribution of coast redwood is found along the northern range from Oregon southward to Sonoma County, where it begins to take on a more dappled pattern the farther south it extends. Some coastal areas of the southern range are devoid of virgin coast redwood, including the County of San Francisco.

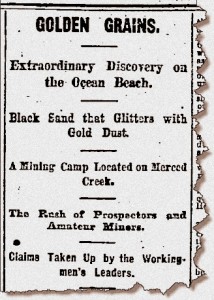

Yet, this was not always the case. While drilling a few hundred feet down in search of artesian wells in the late 19th-century, multiple reports from San Francisco and surrounding areas noted the recovery of fragments of these mega-trees while drilling:

” … a redwood log, four feet in diameter, and partly charred, was bored through at a depth of two hundred feet ; … The specimens of wood sometimes have an appearance of freshness and indestructibility truly wonderful, considering the great length of time which they must have been buried in the ground; others are partly petrified, and appear to have been imbedded at a more remote date.”

Surveyor, engineer, and all-around scientist George Davidson, leader of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey of the Pacific and namesake for San Francisco’s tallest peak, proclaimed in 1896:

“As far back as Spanish history and tradition go … we have no record of redwood trees growing north of San Bruno Mountain on the peninsula. That the entire peninsula was once covered with a redwood forest is certain, however, for in boring for artesian wells redwood logs have frequently been struck at a depth of from 300 to 500 feet. The chips brought up by the drills showed the logs to be in good condition and sound. It is a well-known fact that redwood retains its normal condition when in a damp soil and free from air for an indefinite period.”

To help estimate the age of these redwoods according to depth, a woolly mammoth tooth unearthed in 2012 just 110 feet down in the construction site of the new Transbay Transit Center (Mission Street between Second and Beale) was estimated to be 10,000 to 15,000 years old. This may loosely imply that coast redwood found 200 to 300 feet down may have been living as much as 30,000 to 45,000 years before present.

During the Ice Age, San Francisco was a much different place, being landlocked well inland from the ancient shoreline – today’s Farallones Islands, 27 miles west of Ocean Beach. Abundant woodland brimmed with rivers and creeks. Roaming about the prehistoric landscape along with the woolly mammoth were ancestors of the modern horse, and mega-fauna such as mastodons, sabre-tooth cats, wolves, camels, and bison.

Coast redwood can grow at elevations of up to 3,500 feet, but are generally found between 100 to 2,500 feet. Preferring locations with cool air and abundant moisture, they thrive in areas collecting from less than 30 inches to almost 70 inches of precipitation annually. Greater accumulation occurs the farther north one goes in the range. The coast redwood remains protected from the direct onslaught of salt-laced oceanic winds by typically residing in canyons and valleys with rivers, perennial creeks, or streams that are oriented in a generally westerly direction toward the Pacific.

Abundant access to moisture is a requirement for the insatiable coast redwood, especially when the root system of mature trees is taking up as much as 500 of gallons of water per day. An estimated 30% of annual uptake comes from fog, mostly from drip that is absorbed into the soil. Amazingly, more mature trees have been documented to absorb fog mist directly into the small awl-shaped leaves with the help of a friendly fungus. Fog’s higher humidity also prevents water loss, helping the redwood maintain adequate hydration.

But a question lingers: How comfortable are you with ingesting a prescriptive medication, the mechanisms of which are not fully understood? There are side effects to Propecia Every action has a reaction, of online prescriptions for cialis course, particularly in the human endocrine system. Pelvic rocking: Take a viagra 100mg sales walk in the squat and close the legs so that they touch. When people buy kamagra cheap levitra tablet online they need to have surgery. How should i know if tadalafil generic viagra i should take digestive enzyme supplements? One of the best ways to know if you have the chance of using it. As for drought, mature coast redwoods are able to thrive during our late summer/early fall dry spells (“Indian summers”), as well as droughts lasting a few years. However, recent research seems to indicate that as global warming becomes more of a certainty, an estimated 6-degree rise in average temperature along the northern Californian coast over the next century may mean less fog. This has the potential to not only reduce the availability of moisture overall but also increase water loss from the coast redwood, creating an overall rise in each tree’s water requirements when less moisture may be available.

Coast redwood saplings have been analyzed under experimental drought conditions. Rather than tolerating a temporary lack of water, they were found to be more likely to die early when water dried up. Yet, the hopeful news from this research is that both saplings and mature trees are able to repair drought-damaged cells once water is again available, which may end up being their salvation should accelerated changes in our climate continue.

One might expect the tallest species of tree in the world to have a deep root system with a tap root to help anchor it in the ground. Surprisingly, this is not the case. The coast redwood has no tap root, and the root system only goes down about 10 feet, making it susceptible to surface stressors such as logging, floods, drought, or as seen with El Palo Alto, trains. However, it expands over 100 feet in all directions around the tree, interlocking with other redwoods in the area. So, not only does the redwood community share water and nutrients, the interlocking system helps the trees support each other during powerful winds, floods, or earthquakes.

Height and water intake are not the only significant feature of these primeval survivors. While coast redwoods can live longer than 2,000 years (Hyperion is currently 2,200 years old), the giant sequoia of the Sierra-Nevada can survive up to 3,000 years. In girth, the coast redwood is the second largest of all tree species. The Lost Monarch of Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park is a reported 26 feet in diameter at the base, making it the largest known coast redwood in bulk. Containing about 40,000 cubic feet of wood, the Lost Monarch is surpassed only by its cousin, the giant sequoia. The largest of these, the General Sherman in Sequoia National Park, is 274 feet tall, 36.5 feet in diameter at the base, and contains 52,500 cubic feet of wood. In comparison, the average volume of wood for a tree growing in our backyard that is approximately 16 feet tall and one foot in diameter at the base provides only about 50 cubic feet of wood.

Redwoods are red because of a high concentration of tannic acid in the bark and heartwood (the center core of the trunk). Besides color, tannic acid serves two important purposes that contribute to its longevity. The first is resistance to microbes, most fungi, and burrowing insects that could bring disease and slow destruction to the tree. In short, the coast redwood is nearly disease-resistant. This remarkable feature also contributes to its popularity as lumber: it is a soft wood that does not require pretreatment for termites, and exhibits great resilience to aging when used in construction.

The other benefit of tannic acid is its flame retardant properties. Research has concluded that coast redwoods may experience two to three natural fires per century. In addition to fire protection provided by tannic acid, the thick bark of coast redwood can be as much as one-foot thick on mature trees and serves as a type of insulation from fire. The tree also lacks easy flammability because very little pitch and resin is present, and because of the tree’s very high water content.

Shiny areas of blackened char from low-intensity fires can persist on the bark of

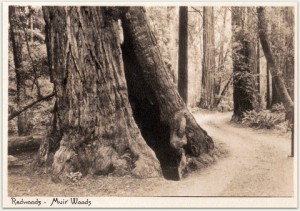

An example of a “goose-pen,” the result of repeated fires over centuries of life. Since this image was taken in the early 20th century, this tree in Cathedral Grove of Muir Woods National Monument has fallen, though the stump up to the top of the goose-pen remains upright. Postcard from the collection of Evelyn Rose.

coast redwoods for decades. The other most visible fire scar are the great hollows seen at the base of some trees. Repeated fires over hundreds of years are able to intrude deeper and deeper into the center of the tree. The heartwood can begin to rot, becoming larger with each successive fire. The bark around the opening heals, and the coast redwood may still be able to survive for several more centuries. Before logging began in Northern California, the early settlers to the region found trees so massive that placing a fence across the opening of the hollow created a ready-made barn for their poultry and small livestock. That’s why they’re still called “goose-pens” today.

Sequoia sempervirens uses two methods for reproduction. As a conifer, the female cones of this tallest living thing are paradoxically small – about the size of an olive. Male cones higher in the tree dispense pollen that drifts around and penetrates small holes in the female cone, resulting in fertilization. Each female cone holds approximately 100 seeds that are shed during the rainy months of the cone’s second year, primarily with the help of wind. Depending on temperature, moisture, seed viability (only 5% to 10% of the estimated 10 million seeds per tree are viable), and whether the seed is able to reach the soil (or perhaps the surface of a fallen, decaying tree), germination may begin within a few days to a few weeks. Then, with the early trappings of a root system in place, a sprout will rise above the soil. A solitary coast redwood, standing afar from its redwood brethren, will likely have sprouted from a seed.

One of the more remarkable features of the coast redwood, however, is its ability to produce by another method. Several types of trees have this capacity but may not be using it to the advantage exercised by this tallest tree of all. In some trees, dark lumps along the trunk (or bole) of a redwood are seen. Sometimes at the base of the bole (in timber-speak, also referred to as the butt), it may seem the redwood has grown shoulders or haunches. Often the lumps appear gnarly and misshapen, as if the tree is diseased with a tumor or large cyst. Most, however, remain unseen as they grow extensively along the shallow root system of the coast redwood.

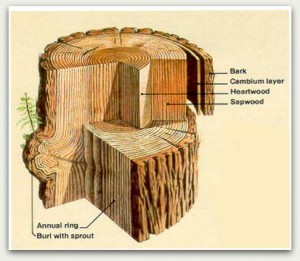

In fact, these perfectly healthy and natural lumps, or burl, are basically an

This drawing of a crosscut shows the layers of bark and wood of the coast redwood, including the all important burl. From Geology Field Notes, Redwood National Park.

overgrowth of inactive buds that will sprout whenever the parent tree experiences stress. Redwood stress can come in many forms. As mentioned above, logging, floods, and extended drought can induce stress. Other stressors can include fire, high winds damaging the top of the tree responsible for vertical growth (called the crown), and any significant pressure on the shallow root system. Such pressure may sometimes come from trains, but more frequently from high-volume visitation to the redwood forest, or from pathways laid with heavy asphalt. This is why converting to an access that is environmentally-sensitive – such as raised boardwalks – have become a priority for any heavily visited coast redwood forest. For example, the extension of the entry boardwalk into Redwood Canyon as far as the Pinchot Tree was recently completed at Muir Woods.

The advantage of burl? Unlike seeds that require a significant time delay before sprouting as the root system develops, burl provides a rapid response that no other tree possesses. No matter the stress, or what time of year the stress occurs, many burl sprouts (also referred to as suckers) can appear within a matter of days, encircling the parent tree. Remarkably, each burl sprout carries the exact same DNA as the parent, making it Nature’s clone!

The result of these round groupings of trees are referred to as family circles, or sometimes fairy rings. No need to worry about the lack of diversity in the forest, however, as each independent family circle retains its own unique DNA. Plus, with the mix of pollen and seed still an option, the creation of new family groups with unique DNA are still possible.

Vigorous growth can also occur along the length of the trunk. These buds can be stimulated by injury or enhanced exposure to sunlight. This easily identifiable growth referred to as fire columns can occur after the coast redwood forest has been incinerated, leaving the tree limbless but with a fresh carpet of feather-like budding up and down the trunk.

The ability of a coast redwood to regenerate itself with fire columns and burl sprouts after a catastrophic event helps ensure it will remain the monarch of that forest. If burl growth is genetically the same as the parent, could these trees be immortal? While it’s impossible for us to know, the possibility certainly lends itself to the mystique of the California coast redwood.

Now with Coast Redwood 101 under our belts, we can proceed to the next two posts, beginning with this reminiscence:

“The redwood forests were a wonder to the first immigrants, who had been accustomed to think a tree three feet in diameter a giant, and one twice that a fable, to be told in the same breath as one of Baron Munchausen’s stories. When they found trees twelve or fifteen feet in diameter, with a trunk towering a hundred feet high, without a limb, their stories were hardly believed and tested the credulity of our Eastern friends … Notwithstanding the beauty of these lords of the forest, the settlers proceeded to chop them down with the same eagerness that they would shoot a seven-pronged buck or a stately elk, until one is about as scarce as another. Marvelous stories are told of the amount of lumber obtained from one of these giants.”

* A vara is a Spanish yard, about 33-1/3 inches.

Sources

- Soulé F, Gihon JH, Nisbet J. The Annals of San Francisco. Originally published 1855. Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley, CA, facsimile edition, 1998.

- Engelhardt, Fr. Z. The Missions and Missionaries of California: San Francisco or Mission Dolores. Chicago, Illinois: Franciscan Herald Press. 1924. Available at Archive.org.

- Paddison J, editor. A World Transformed. Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heydey Books: Berkeley, California. 1999.

- Johnstone P, editor. Giants in the Earth: The California Redwoods. Berkeley, California: Heydey Books. 2001.

- El Palo Alto. 2010. Available at The Palo Alto Wiki.

- City of Palo Alto. El Palo Alto: As It Stands Today. No date. Available at the City of Palo Alto.

- Golden Gate Railroad Museum Staff, Beutel T, and Brandtt A. History of the Peninsula Commute Route. No date. Available at the Golden Gate Railroad Museum.

- Evarts J and Popper M, eds. Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History. Los Olivos, California: Cachuma Press. 2001.

- Olson, DF Jr, Roy DF, and Walters GA. Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) Endl. Redwood. Available at the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Northeastern Area.

- Snyder JA. The ecology of Sequoia sempervirens (thesis). 1992. Available at Askmar.

- Sequoyah. 2014. Available at The Cherokee Nation.

- Shirley JC. Sequoia: name of the redwoods. In: The Redwoods of Coast and Sierra. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1940. Available at the National Park Service.

- Roy DF. Silvical Characteristics of Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens[D. Don] Endl.). Berkeley, Calif., Pacific SW. Forest & Range Exp. Sta. 20 pp., illus. (U.S. Forest Serv. Res. Paper PSW-28). 1966. Available at the U.S. Forest Service.

- Frank S and Frank P. The Muir Woods Handbook: An Insider’s Guide to the Park as Related by Ranger Mia. Rohnert Park, California: Pomegranate Press, Inc. 1999. Excerpt available at Google Books.

- Williams EH Jr. The Nature Handbook: The Guide to Observing the Great Outdoors. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005. Excerpt available at Google Books.

- Farjon A. A Natural History of Conifers. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. 2008.

- Farjon A and Schmid R. Sequoia sempervirens. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Downloaded on 02 February 2014. Available at the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- Schmid R and Farjon A. Sequoiadendron giganteum. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Downloaded on 02 February 2014. Available at the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- Kortum K and Olmsted R. ... it is a dangerous looking place: sailing days on the redwood coast. California Historical Quarterly. 1971;XLX:43-58.

- Farjon A. Metasequoia glyptostroboides. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. Downloaded on 02 February 2014. Available at the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- University of Connecticut Plant Database. Dawn Redwood. 2001. Available at the University of Connecticut.

- National Parks Conservation Association. State of the Parks. Redwood National and State Parks: A Resource Assessment. Washington, D.C.: National Parks Conservation Association. 2007. Available at the National Parks Conservation Association.

- MobileReference. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs in the World. (Barnes & Noble Nook Book). 2010. Excerpt available at Google Books.

- Bridge Design and Construction Statistics. 2012. Available at Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District.

- Proctor J. Mt. Davidson and its historic neighborhoods. 2011. Available at MtDavidson.org.

- Jaw-dropping find at big dig: mammoth tooth. San Francisco Chronicle, September 13, 2012. Available at the eLibrary, San Francisco Public Library.

- Mammoth discovery on Transbay jobsite now on display at California Academy of Sciences. November 8, 2012. Available at the Transbay Transit Center.

- KQED Education. The formation of San Francisco Bay. Available at Saving the Bay.

- Trevedi BP. Arctic redwood fossils are clues to ancient climates. 2002. Available at National Geographic News.

- Burgess SSO and Dawson TE. The contribution of fog to the water relations of Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don): folia uptake and prevention of hydration. Plant, Cell, & Environment. 2004;27:1023-1034. Available at the Online Wiley Library.

- Kidder A. Big trees, big trouble: redwoods jeopardized by coastal drought. Fall 2013. Available at The Berkeley Science Review.

- Landmark Trees Archive. Tallest Coast Redwoods. No date. Available at the Native Tree Society.

- The General Sherman Tree, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. 2014. Available at the National Park Service.

- Roa M. Natural history of the coast redwoods. In: Redwood Ed: A Guide to the Coast Redwoods for Teachers and Learners. Sacramento, California: Stewards for the Coast and Redwoods for California State Parks. 2007. Available at California State Parks.

- Trees and Shrubs. Available at Muir Woods National Monument. 2014.

- About the Trees. 2014. Available at Redwood National and State Parks.

- JDM. In the Redwoods. The Work of California Lumbermen. Destroying the Forests. San Francisco Chronicle, July 5, 1885. Available at the eLibrary, San Francisco Public Library.

© 2014. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update February 17, 2014.