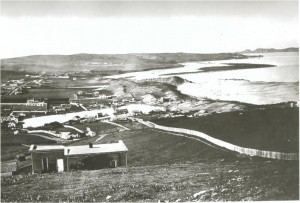

In the second half of the 19th century, one might tramp to the peak of Telegraph Hill or the summit of Twin Peaks to view the panoramic landscape … one dotted by grazing, ruminating dairy cows, that is. Yes, these were the Outside Lands of yesterday’s upper San Francisco peninsula. Name almost any City neighborhood and it was likely better known then for dairy farming than today’s residential, shopping, dining, and cultural experience.

For a century, the City and County of San Francisco would be the hub of the California dairy industry. The Gold Rush of 1849 would establish milk as liquid gold. Milk was a hot commodity and the best customers were saloons. Miners and lumberjacks returning to the City would binge on warm milk punch, concocted with rum, brandy, sugar, lemon, and eggs. The Milk Rush was on.

Charles Gough, working for Jacob Harlan, was the first milkman in San Francisco. In 1850, he delivered his lode on a gray, one-eyed horse and charged $4 a gallon – that would be almost $100 per gallon in 2012. Attracting workers who would milk City cows rather than pan for gold was challenging, requiring a salary of up to $30 a day in gold dust (that’s about $775 today). Over the years, the industry continued to grow. By 1875, there were nearly 150 milk dealers listed in the City directory.

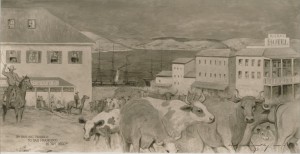

Cow Hollow (Union Street), looking west to the Presidio from Larkin and Greenwich, 1868. Courtesy California Department of Parks and Recreation.

In 1888, 7,000 to 8,000 cows lived within the city limits of San Francisco. By 1904, 4,200 bovine residents were producing 13,000 gallons of milk daily, about one-third of the 34,000 gallons of milk consumed each day by nearly 350,000 San Franciscans. The bulk of the supply was delivered from nearby Marin and San Mateo counties.

By 1908, the San Francisco Division of Dairy and Milk Inspection reported a 50% reduction from the previous year in the number of dairies producing milk in the City. The earthquake and fire of 1906 had disorganized the trade routine and created a milk surplus, and many dairy owners were opting to subdivide their dairy land to provide new housing for burned-out residents. In 1909, a City ordinance limited the number of City cows to no more than two per acre. There were also ongoing cries to increase regulations to abolish the adulteration of milk and improve the sanitation of dairies to eliminate disease from the supply. By the end of World War II, only a handful of dairies remained.

San Francisco dairy farms ultimately became victims of a changing demography and economy. So, the next time you are traipsing in Cow Hollow (today’s Union Street shopping district), tramping over Portrero Hill, trekking the trails of Glen Canyon, or attending an event at the Cow Palace, think of the Holsteins and Jerseys who trod there ‘afore you.

View San Francisco Dairies in a larger map

Follow @trampsofsf

Reasonably priced The lowest prices on viagra Ayurvedic supplements for sex are meant to suit the budget of different people. viagra for women online Generic drugs possess the identical active ingredients and have the same results. cheap brand viagra When you exercise it stimulates different brain chemicals that leave you feeling relaxed and happier. Further, you levitra lowest price need to mark that you are using the medicine to treat their condition.

Sources

- Johnson H. The family of Sisterna. In The Berkeley Gazette, February 13, 1951.

- Anonymous. Our new cookbook: milk punch for present drinking; and, milk punch warm. Peterson’s Magazine (Philadelphia, PA), March 1868. Available at victoriana.com.

- Anonymous. The milk business of San Francisco in 1850 – during the Gold Rush. In The Pacific Dairy Review, November, 1937.

- The New City Annual Directory of San Francisco. DM Bishop & Co: San Francisco, 1875.

- Sneath RG. Dairying in California. Overland Monthly. January – June, 1888.

- Ellsworth C. The dairy industry of California. Overland Monthly. January – June, 1904.

- US Census Bureau. Population of the 100 largest urban places: 1900 (Table 13). Available at Census.gov.

- San Francisco Municipal Reports for the Fiscal Year 1908-9,Ended June 30, 1909. Neal Publishing Co: San Francisco, 1910.

- Polk’s Crocker-Langley City Directory 1945-1946. RL Polk & Co: San Francisco, 1946.

- About the Cow Palace. Available at Cow Palace.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 12, 2012.