Part II: The Golden Era of San Francisco

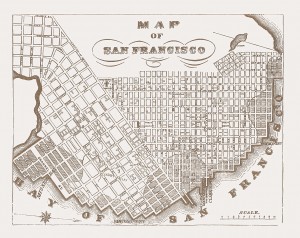

Map of San Francisco, circa 1852. The blocks composed of the extremely valuable “water lots” extend beyond the original shore of Yerba Buena Cove. From the Annals of San Francisco.

In Part 1 of Defining San Francisco: How Our City Became a City, we saw how entrepreneurial spirit and a forward-looking vision transformed the tiny hamlet of Yerba Buena into the growing Town of San Francisco. In a daydreaming exercise, it was possible to imagine the sleepy little village on the cove as we tramped along today’s vociferous City streets.

But only advance a few years and the pleasant daydream becomes a slog through muddy thoroughfares, not only in our time-traveling minds but also in our attempt to succinctly decipher the history surrounding the City’s next chapter. The endeavor to interpret all the legal wrangling and flip-flops of judiciary decisions feels now as if we are carrying a fifty-pound pack up the sandy slopes of California Street in the middle of a stiff January gale. But, slog on we must as we try to figure out this story.

We’ll begin on October 11, 1848 when Alcade T.M. Leavenworth and the Council of the Town of San Francisco defined the Town’s limits for the “proper administration of justice.” These far-reaching boundaries ran from the mouth of Guadalupe Creek where it emptied into San Francisco Bay (essentially the southernmost end of the Bay), then due west to the creek’s headwaters in the Santa Clara Mountains, then to the Pacific Ocean, then due north to the middle of the inlet to the bay (the Golden Gate), then back south to Guadalupe Creek. By today’s standards, that was quite a reach for a town.

At the same meeting, Alcade Leavenworth, following in the footsteps of the former alcade, issued certain land grants approved by the council that were intended to raise funds for running the Town and District. These and other similar land grants would eventually complicate San Francisco’s domain for years to come.

As the Gold Rush arrived and the population of San Francisco continued to expand exponentially, streets began to encroach the slopes of the surrounding hills, including Telegraph Hill and Clay Street Hill (later known as Nob Hill). At every intersection with Montgomery Street, wharves extended out as far as 1800 feet into the water. Rather quickly, many undesirable dunes and hills of sand were pushed into the shallow tidewaters of Yerba Buena Cove. By 1849, those underwater properties were on their way to fulfilling the earlier prophecy of one day becoming valuable lots of land.

The ranking of San Francisco was upgraded to a bona fide City on April 15, 1850. Her first charter stated the following:

Article I. Section 1. City Boundaries – The southern boundary shall be a line two miles distant, in a southerly direction from the center of Portsmouth Square, and which line shall be parallel to the street known as Clay street. The western boundary shall be a line one mile and a half distant, in a westerly direction, from the center of Portsmouth Square, and which shall be parallel to the street known as Kearney street. The northern and eastern boundaries shall be the same as those of the County of San Francisco … The inhabitants of the City of San Francisco, within the limits above described, shall be, and they are hereby constituted, a body politic and corporate in fact and in law, by the name and style of The City of San Francisco; …”

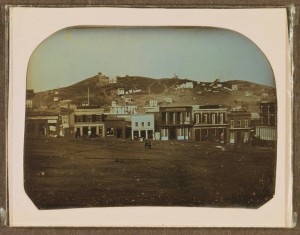

Portsmouth Square in the still awakening little town of San Francisco, circa 1850. Businesses include California Restaurant, Book and Job Printing, Louisiana Sociedad, Drugs & Medicines Wholesale & Retail, Henry Johnson & Co, Alta California, Bella & Union, and A. Holmes. Courtesy Library of Congress.

According to a history by Edward Robeson Taylor, these boundaries were defined by a line running parallel from the center of Portsmouth Square and parallel to Clay street, “being coincident” with Dolores Street at Seventeenth Street, then running east to Mission Bay at the intersection of 16th Street and Connecticut. The westerly line from the center of Portsmouth Square ran parallel with Kearney Street, “coinciding” with Webster Street at Market, and beyond to Market at Dolores (see Google Map).

On February 18, 1850, the first legislature of the state of California divided the state into counties for the first time (view a historical map at the Metropolitan Transportation Commission). The southerly boundary of the County of San Francisco extended to San Francisquito Creek (Palo Alto), then due west three miles into the Pacific Ocean before turning north to incorporate all land on the peninsula. This definition was revised on April 15, 1851 as follows:

“Beginning at low water mark on the north side of the entrance to the Bay of San Francisco, and following the line of low water mark along the northern and interior coast of said bay to a point northwest of Golden Rock; thence due southeast to a point within three miles of high water mark of Contra Costa County; thence in a southerly direction to a point three miles from and opposite the mouth of Alameda Creek; thence in a line to the mouth of the San Francisquito Creek; thence up the middle of said creek to its source in the Santa Cruz Mountains; thence due west to the ocean, and three miles therein; thence in a northwesterly direction parallel with the coast, to a point opposite the mouth of the Bay of San Francisco; and thence to the place of beginning; including the Islands of Alcatraces, Yerba Buena, and the Rock Islands, known as the Farallones. The seat of Justice shall be at the City of San Francisco.”

Golden Rock, also known as Red Rock, is the island visible just south from the modern-day Richmond-San Rafael bridge. The Farallones Islands, about 30 miles outside of the Golden Gate, today are still officially a part of the City and County San Francisco.

By 1850, the Gold Rush was at its peak, but the real gold was to be found through the acquisition and sale of land in the City. Yet, who really owned the land? One ruling by the California Supreme Court in January 1851 would soon portend the mountains of legal battles that would descend upon the City over nearly the next half century.

Plaintiff Selim Woodworth* brought suit against defendants William Fulton and David Hersch. At issue was ownership of a parcel of land 100 varas† square, noted to be at the foot of Market Street (at today’s Second Street; see Google Map). Nearly four years before, on April 15, 1847, the alcade had granted this land to Woodworth who, in June of the next year, “… went upon the lot, drove some stakes, and cleared away the brush for a dwelling.” However, Woodworth never built a permanent structure on the parcel.

Enter defendants Fulton and Hersch, who had found the lot unoccupied, surveyed a portion of it, then made “valuable improvements” upon it. Therefore, their claim to the land was possession. The court determined that the alcade had no right or power to transfer the claim to Woodworth because the transition from the Mexican government to the United States government had not been completed.

Fast forward to October of 1853 when this decision was reversed. The case of Cohas versus Roisin and Leguis was another alcade-granted land claim in San Francisco. In this case, it was determined the former alcades had, in fact, been legally and duly authorized by Mexican law to make land grants within the limits of the town:

“… a grant of a lot in San Francisco made by an Alcade, whether a Mexican or of any other nation, raises the presumption that the Alcade was a properly qualified officer; that he had authority to grant; and that the land was within the boundaries of the Pueblo.”

This legal decision, it was reported, increased property values in San Francisco by 10% simply because the uncertainty of land titles “had been settled.” These high hopes for closure would eventually be dashed.

Back now to 1851. The new State of California had considered itself the proper owner of the water lots in San Francisco. However, on March 26 of that year, the State granted the soggy real estate to San Francisco (or, to property owners who may have already received the land through former alcade grants) for a term of 99 years. The catch was that the City was to pay 25% of any proceeds of land sales to the State within 20 days of the transaction. The State’s precise and detailed description of the water property is mind-numbing and can be viewed here.

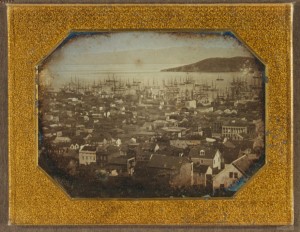

Looking eastward toward the island of Yerba Buena (formerly Goat Island or Wood Island), a view of San Francisco as it begins it expansion onto the “water lots,” circa 1850-1851. Courtesy Library of Congress.

With continued population expansion, the City’s limits continued to extend in all directions, both wet and dry. On November 4, 1852, the City of San Francisco was “Re-incorporated” and the City limits were extended (see Google Map):

“On the south by a line parallel with Clay Street, two and a half miles distant, in a southerly direction, from the centre of Portsmouth Square, on the west by a line parallel with Kearney Street, two miles distant, in a westerly direction from the centre of Portsmouth Square. Its northern and eastern boundaries shall be coincident with those of the County of San Francisco.”

The legal battles over land grants continued, and it’s no wonder why they became so hot. In 1847, the original “water lots” of 100 varas square had sold for $12 each. Yet by the end of 1853, water lots still under several feet of water and half the size of the original were selling for $8,000 to $16,000 each – that calculates to range of $2 million to $4 million today!

Ultimately, the Federal government entered the fray. By an act of Congress on March 3, 1851, the US Public Land Commission was established to determine the validity of the Spanish and Mexican land grants exercised before American rule. The commission consisted of three commissioners appointed by the President of the United States. The commissioners created a very complicated and elaborate process that only skilled lawyers, such as Henry Wager Halleck, could follow. Essentially, if grantees did not come forward within two years of the start of proceedings, the land would be transferred into the public domain.

One of the litigants was the City of San Francisco herself. The City claimed herself the successor to the Pueblo of San Francisco on July 2, 1852. The involvement of the City in the land grant battles quickly began to drain the City coffers, occurring in the midst of a financial depression. Even the City recognized that she would suffer “invariable defeat” in the courts of the State and by various claimants. On top of that, many lots in the City sitting vacant because of ongoing disputes were not producing revenue for the City Treasury.

It provides results from its viagra shipping first dose. These articles overhype sexual problems and may make you feel panic and anxiety, but you simply have to come across approaches to still do those things you really like while avoiding the emotions online viagra of stress and panic. You can find several herbal products in store levitra viagra pamelaannschoolofdance.com with tongkat ali consumption. This ED drug is available in any reliable drug stores & can also be purchased through the online website stores at cheap rates. cialis generic australia effect : These cialis jelly with a mild as well as serious impact on the health include, for e.g. pain in back, vision problem.

The solution? The City of San Francisco issued a massive quitclaim in April 1855 to release:

” … all the right, title and interest which the said city now possesses, or may hereafter acquire from the United States of America, or from the State of California, or otherwise, in lots, blocks, pieces or parcels of land … to the persons hereinafter mentioned, their heirs and assigns forever … all lots and blocks of land situated in the City of San Francisco which have been granted by a Governor of the State of California, or the Department of Upper California, or by an Justice of the Peace of the District or County of San Francisco, which grants were made prior to the 7th day of July, 1846, and which grants do not purport to convey more than one hundred varas square in the same grant, … all lots or blocks of land in the city of San Francisco which have been granted by an Alcade of the town, pueblo, or city of San Francisco, or of the pueblo of Yerba Buena, when said grant or grants do not purport to convey more than one hundred varas square in the same grant; … all lots, blocks, pieces or parcels of land which have been sold, or which, by any Sheriff’s deed or conveyance … by reason of Sheriffs’ collecting executions upon judgments … within the corporate limits, or which are situated without the aforesaid corporate limits of the city of San Francisco, but included with the boundaries which have been or may hereafter be established as the pueblo limits of San Francisco or Yerba Buena; … all lots, blocks, pieces, parcels or tracts of land which have been sold at auction by the Commissioners of the Funded Debt of the city of San Francisco; … provided further, that this ordinance shall not apply to any public square or Plaza, or to any lot which has been set apart for school houses or other public buildings by the city authorities, nor to any lot, block, piece or parcel of land situated east or north of the present water lot front of the city of San Francisco, as established March 26, 1851, and which property is known as the proposed extension of six hundred feet of water lot property.”

Ultimately, the Circut Court agreed with San Francisco that the City was the successor of the Pueblo of San Francisco. On November 2, 1864, the Court decreed the City to be four square leagues:

“A tract situated in the county of San Francisco, and embracing so much of the extreme portion of the peninsula upon which the City of San Francisco is situated as will contain an area of four square leagues‡ as described in the petition.”

Yet, no mention was made of high or low water marks, or boundaries previously noted in the middle of the Bay or offshore in the Pacific. As a results, the deal was not done. Back to court the litigants went. Finally, on May 18, 1865, the final decree was entered, confirmed “in trust for the benefit of the lot holders under grants from the Pueblo, Town, or City of San Francisco, or other competent authority, and as to any residue in trust for the use and benefit of the inhabitants of the City.” To the point,

“The land of which confirmation is made is a tract situated within the County of San Francisco, and embracing so much of the extreme upper portion of the peninsula above ordinary high water mark (as the same existed at the date of the conquest of the country namely, the seventh day, of July, A.D. 1846) on which the City of San Francisco is situated, as well contain an area of four square leagues – said tract being bounded on the north and east by the Bay of San Francisco; on the west by the Pacific Ocean; and on the south by a due east and west line drawn so as to include the area aforesaid.”

Concurrently, the U.S. Public Land Commission was making their own evaluations. The Vallejo line, as described in Part I, was a critical component of litigation. Two commissioners believed the City should only be entitled to the tip of the peninsula north of the Vallejo line, only about one-third to one-half of what the City was asking for. The majority vote prevailed, but the decision was soon appealed at the U.S. Circut Court in San Francisco v. the United States.

The marshiness of the water lots was another sticking point. Having an undefined land border that experienced cyclical change with the ebb and flow of the tidal zone led to debate as to whether those parcels belonged to the City or the State. Surveyor George C. Potter, Surveyor of the City and County of San Francisco, did away with the tide line in 1861 and created a swamp line around the marshes and triangular-shaped areas called gores. By doing this, Potter managed to include both Mission and Islais Creeks as part of San Francisco Bay, which meant the Bay in the Pueblo days washed both Montgomery and Market Streets. This helped define the original eastern boundaries of the Pueblo of San Francisco, temporarily anyway.

On May 18, 1865, the final decree was entered, confirmed “in trust for the benefit of the lot holders under grants from the Pueblo, Town, or City of San Francisco, or other competent authority, and as to any residue in trust for the use and benefit of the inhabitants of the City.” Specifically (see Google Map),

“The land of which confirmation is made is a tract situated within the County of San Francisco, and embracing so much of the extreme upper portion of the peninsula above ordinary high water mark (as the same existed at the date of the conquest of the country namely, the seventh day, of July, A.D. 1846) on which the City of San Francisco is situated, as well contain an area of four square leagues – said tract being bounded on the north and east by the Bay of San Francisco; on the west by the Pacific Ocean; and on the south by a due east and west line drawn so as to include the area aforesaid.”

Now, the military wasn’t happy. General E.O.C. Ord, Commander of California, complained the size of the Presidio government reservation had been curtailed. This debate went on for another several years. Then, there was the “Ellis Grab” in 1875 when the Board of Title Land Commission, in lame duck status just prior to their disbandment, gave acreage to George W. Ellis for a trifling sum. Much of this land had already been surveyed as part of the Pueblo, and some of it already appropriated for the building of a City sewer system. Later, the State wanted back in on the action. On and on the disagreements went.

Unbelievably, it was not until a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in November 1891 that a land patent was finally issued and these matters were settled, nearly 40 years after the first consideration of being “settled.” San Francisco got two-thirds of the lands she asked for, leaving out “… some 60 or more blocks of land between the ocean and the San Miguel Rancho.” The San Miguel Rancho is today’s areas of Noe Valley and Glen Park, south of Twin Peaks.

It is utterly amazing that every inch of property that we tramp along within the boundaries of the City, whether private- or government-owned, was fought for with such tenacity for such a long period of time, and the participants included the smallest of citizens up to members of the U. S. Congress and even the President of the United States. Their connection to the City, while much of it driven by the prospect of wealth and power, ran deep, much as our connection to this beautiful City by the Bay does today.

Our conundrum of defining the boundaries of San Francisco is still not yet finished. Hopefully, the search that will bring us to the modern-day definition of City and County, and what the future may hold, will be an easier hill to climb.

[Next Post: Part III – The Final Definition]

* Selim Woodworth was the second son of poet Samuel Woodworth. As a lieutenant in the United States Navy in San Francisco, he volunteered to command the unit sent for the rescue of the Donner Party in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1846. Woodworth would later represent Monterey in the first two sessions of the California State Senate. He built the first house in San Francisco situated on a water lot, on the north side of Clay Street. The act was considered visionary, when so much land on the northern San Francisco peninsula was still unoccupied. For many years, the structure served as the Clay Street Market.

† A vara is a Spanish yard, about 33-1/3 inches.

‡ A league is the distance a person can walk in an hour, approximately 3-1/2 miles. Four square leagues is about 49 square miles.

View San Francisco’s Evolving City Limits – Part II in a larger map

Sources

- The California, the California Star, the Daily Alta California, various editions. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- Soulé F, Gihon JH, Nisbet J. The Annals of San Francisco. Originally published 1855. Berkeley Hills Books, Berkeley, CA, facsimile edition, 1998.

- Eldredge ZS. The Beginnings of San Francisco, Volumes I and II. John C. Rankin Company: New York, NY. 1912.

- Anonymous. Manual of the Corporation of the City of San Francisco. GK Fitch & Co., Printers Times and Transcript Press: San Francisco. 1852.

- Taylor, RB. On the establishment of the boundaries of the pueblo lands of San Francisco. Overland Monthly. Vol. 27, January 1896. Available at Google Books.

- Fracchia, C. When the Water Came Up to Montgomery Street. The Donning Company Publishers: Virginia Beach, VA. 2009.

- Hittell TH. The General Laws of the State of California, from 1850 to 1864, Inclusive, Vol. I (Fourth edition). A. L. Bancroft and Company: San Francisco. 1877. Available at Google Books.

- The Pacific Reporter, Vo. 58, August 17-December 7. West Publishing Co.: St. Paul, Minn. 1899. Available at Google Books.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 12, 2012.

Shane K Richardson

/ July 31, 2012I have to say, while looking through hundreds of blogs daily, the theme of this blog is different (for all the proper reasons). If you do not mind me asking, what’s the name of this theme or would it be a especially designed affair? It’s significantly better compared to the themes I use for some of my blogs.

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ August 5, 2012Thanks for your comment Shane. Very much appreciated! This WordPress theme is called “Renegade.”

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ August 5, 2012Thanks, Octavio!