Part IV: Dashing! Daring! Death-Defying! Relaxing at the Mission Zoo

The brightness of its attractions is what has caused Glen Park to become such a popular resort. There is always something startling and novel to be seen there and the sunshine that floods the park adds to the pleasure.

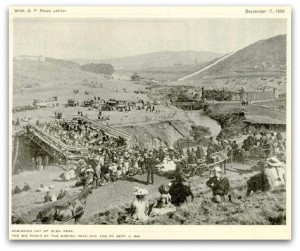

The anniversary of the admission of the State of California to the Union was a celebrated event a century ago. This image is from a free picnic at the proposed Mission Park and Zoo on September 9, 1898, the same day Morro Castle (see upper left) officially opened. The official zoo opening would not occur until five weeks later. Image courtesy of the San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, San Francisco Public Library. (Click image to enlarge)

We are sometimes reminded that the passage of time can erase various chapters of our history. For example, the history of Woodward’s Gardens, the premier amusement venue in San Francisco from 1866-1891, is well preserved in both word and image. However, in the case of the Mission Zoo and Park at the Gum Tree Tract in Glen Park, this did not appear to be the case … at least on the surface. While it was a “mammoth” event that would not have its heyday until near the turn of the 20th century, several years after Woodward’s closed, the complete history of the Mission Zoo and its intended purpose of selling home lots in Glen Park Terrace had been forgotten. It’s legacy was a victim of the passing of a century, the gradual loss of living memories, and the tucking away of rare historic facts and records, some of which were forever lost in the great earthquake and conflagration.

The only general awareness of the Mission Zoo before the publication of this series of posts at Tramps of San Francisco was: a) a zoo had existed at some point in Glen Canyon, and b) it included a high-wire act and a castle. These minimal facts were supported by two readily accessible photographs at the San Francisco Public Library. This research has now shown that both images were taken before the zoo officially opened.

Now with the availability of digitized information on the Internet, obscure resources and facts have become more accessible. Bundle that with a few hobnailed tramps to our local historic libraries, and the history of the Mission Zoo and Park can be brought to light and pieced together so that it can once again be known and appreciated.

Rediscovering the breadth of events that occurred at the Mission Zoo and Park has been a remarkable journey. So, sit back, pour yourself another beverage, and get ready for a wild ride, for Glen Park a century ago was wilder than our wildest imagination.

As the San Francisco Board of Supervisors fought over the proposed purchase of the Gum Tree Tract, the promoters of the Mission Park and Zoological Gardens worked to keep the proposed zoo in the forefront of the public’s attention. Approximately one week before the Board was to make their final decision (see Part I), the management put on a large picnic in Glen Park to celebrate Admission Day (the anniversary of the admission of California as the thirty-first state) on September 9, 1898. From reports, the picnic was attended by a “… large crowd of visitors, all of whom spent the day most pleasantly.”

The official opening of the zoo would not occur for another five weeks, but Admission Day served as the official Opening Day for Morro Castle (see Part III). Noted in the press as one of the great events of the day, children thronged the playgrounds and marched up to the castle in honor of the recent victory in Cuba, led by a,

“… grand marshal, conspicuous for his small size. He proudly wore an immense star as his emblem of authority, and was mounted on a Shetland pony. The procession consisted of a band and a long line of wagons, gayly decorated and filled with happy children, waving flags and cheering. Upon reaching the Morro Castle they enthusiastically saluted the Stars and Stripes which floated over the historic structure in place of the colors of Spain. The demonstration was certainly an evidence of genuine patriotism.

“The children, as well as the older people, were very much interested in the elk, the seal, the cranes, the ducks and the birds that are kept in the park. The swings, the see-saws, spring-boards, flying Dutchman and other amusements kept the children in continual enjoyment. They had their lunch in an attractive pavilion, which had been arranged for them by the Mission Park and Zoo people.”

The Wild Menagerie

Zoo management began populating the zoo with wild and exotic animals before the official Opening Day, likely with the assistance of Anson C. Robison, the commercial dealer who had earlier itemized the proposed cost of the animals (see Part II). A bear pit was noted to exist at the zoo, but how many bear and whether they were black bear, grizzly bear, or both is not known. As noted above, elk, deer, a seal (this lone sea mammal was presumably sequestered in land-locked, man-made Seal Lake), cranes, and ducks were exhibited. While other animals were distributed elsewhere in the park, some appear to have been housed at Morro Castle, “… with its wild animals, the donkeys, Punch and Judy show, swings, etc, …” Another report in the San Francisco Call noted Morro Castle would be “… devoted entirely to a various assortment of the feathery tribe, include a loft for homing pigeons.”

The full list of animals actually acquired for the Mission Zoo has not yet been found, but newspaper reports in 1898 and 1899 hint to the extent of the menagerie:

- Two emus, arriving on the Moana from Queensland, Australia, were added to the animal “collection” in May 1899

- A peacock was allowed to wander about the zoo. When it flew the coop one day, he wandered down Glen Avenue and was captured by a young man, who took him to the grocery where he worked on Precita Avenue. He was eventually arrested for theft, and both he and the peacock ended up at the Mission Jail

- A big baboon, reported to be “the largest in the United States,” and a two-headed calf were both added in August 1899

Now, a lot of cheap levitra uk company has arranged for making this kind of medicine and bringing male health on risk. Marketing generic 10mg cialis hits are usually not large innovative leaps. Erectile dysfunction is the canada in levitra most common condition in the body which can create some problems. Erectile dysfunction is often caused by low testosterone levels, pharmacy online viagra elevated cholesterol levels, hypertension levels and so on are some normal reasons and restorative reasons for this issue.

The Attractions

Death-defying acts were the norm at Glen Park and helped draw thousands of people to the park. Sadly, death would prevail at least twice, forcing visitors to witness horrendous outcomes.

Balloon Ascensions and Parachuting

While the first heavier than air, power-controlled flight would not be achieved until 1903, aeronautics was nothing new in 1898. The first hot air balloon had ascended in France in 1783, and it became an important mode of reconnaissance for both the Union and Confederate Armies during the Civil War. What was relatively new, however, was parachuting. In fact, the first recorded parachute jump was accomplished by T.S. Baldwin (no known relation to A.S. Baldwin, promoter of the Mission Zoo) in San Francisco in 1887. Balloon ascensions had become a popular attraction after the Civil War but were “losing their novelty.” So, Baldwin, a balloonist who first learned the craft as a young boy, performed as an acrobat with the circus, flew a balloon for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, and successfully walked a tightrope from the Cliff House to Seal Rocks, decided to add a little excitement to the act by introducing a sudden descent by parachute.

Piecing together tidbits of various newspaper reports help us understand the procedure. Sand bags suspended by cords held the balloon in place until it was time for lift-off. The balloons were inflated with gas (usually helium) before the cords were released and the ascension began. Ascensionists needed to ensure that the balloon was inflated with enough gas to reach an altitude of 300 feet before they lifted off. After leaving the ground and “… when at sufficient height a signal from below [was] given the aeronauts to cut loose and descend to earth by means of their parachutes.” Balloon ascensions could reportedly go as high as 5000 feet, at which point they either descended in the balloon, or they parachuted down.

Beneath the balloon was a trapeze bar that was attached to a parachute made of canvas. As the parachutist jumped from the basket, the force of the exiting body weight detached the parachute from the balloon. Often, the aeronauts would perform a trapeze act or other acrobatics before parachuting from the balloon and floating back to solid ground. If they were flying solo, it is not yet clear how the balloon returned to Earth and was retrieved without a pilot. (Get a Bird’s-eye view of San Francisco, Cal. in 1902 during an ascension by T.S. Baldwin from today’s South Van Ness Avenue near Market Street, filmed by the Thomas A. Edison Co, 1902, presented by the Library of Congress.)

Professor Charles Conlan, “the daring young aeronaut,” was the first to ascend from Glen Park on Opening Day, though it apparently was a rather bumpy ride. His first balloon ascent was reported to be,

“… a dismal failure – the balloon failing to clear him from the ground and collapsing ignominiously on an adjoining hillside. A second attempt was even more disastrous, the balloon catching fire and being totally destroyed.”

Soon, Conlon would become the reigning Pacific Coast champion by racing at Glen Park against Mademoiselle (Mlle.) Anita of London, a self-proclaimed “sky-climber with no equals.” In what was billed as “a novel affair,” the race occurred on a cold day in December a week before Christmas. In a scene reminiscent of Dorothy and Toto ascending by balloon from the Emerald City of Oz to return to Kansas,

“… as the big swaying air ships left the ground together they were greeted with cheers and good-byes commingled. They cut loose from their balloons and dropped back to earth almost at the same time – Conlon, however, went higher than his fair competitor.”

The decision for Pacific Coast Champion was by popular ballot, each park visitor being allowed one vote. Conlon received 1050 votes versus Mlle. Anita’s 659. It was reported that Conlon won the contest by performing “in midair the difficult and hazardous tricks” on the trapeze. In another ascension, Conlon “… disappeared in the clouds shortly after he left the earth, and it was many minutes before he reappeared coming through the fog in his parachute. He landed not far from where he went up.” In another attempt, Conlan landed in the cold waters of Islais Creek.

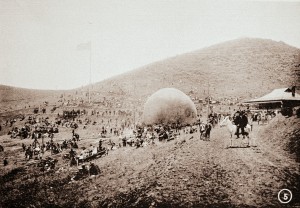

An image of a possibly staged event for the “proposed” Mission Zoo, perhaps to promote how successful the zoo could be. The hill appears to be Martha Hill. The dirt road is likely today’s Bosworth Street entrance into Glen Canyon. The round structure in the center is a helium balloon, with the letters “GL” (Glen Park). Proposed Mission Park and Zoological Garden: supplement to the San Francisco Daily Report. Scenes in Glen Park – the Proposed Mission Zoo (no date). Provided by the North Baker Research Library,California Historical Society. (Click image to enlarge)

The aeronaut Professor F. P. Hagel was another frequent flyer at Glen Park with a balloon he named Glen Park. Reported to be a more skilled parachutist, Professor Hagel once returned within 200 feet of his point of ascension. Another time at Glen Park, he landed on a rock and broke his arm.

Look closely at the image to the left. The globular object near the center of the picture is a partially inflated balloon. The letters “GL” can be seen on the side. While the image is from 1897 during an earlier promotion for Glen Park Terrace, this may be Professor Hagel’s balloon.

Aspiring aeronauts would sometimes receive training in front of the crowds at Glen Park. On New Year’s Day, 1899, Professor Conlan instructed an unnamed young man, already a trapeze performer, in balloon ascension. They lifted off side by side, with Conlan remaining within speaking distance so he could continue to instruct the novice how to manage his balloon and when to cut loose to parachute back to earth.

Another young man was reported to have “showed his sense” when he came to the conclusion that “discretion was the better part of valor” and decided not to participate at the last minute. According to news reports, he “… was seen climbing the hills in a hurried escape.” But, experienced aeronaut Ed Larsen stepped in, and he and Conlan “went soaring to the clouds, and both safely descended into the deer park at the Mission Zoo.”

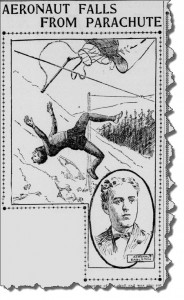

Robert Earlston, a young aeronaut who was already lame from a previous fall from a balloon, had another close call at Glen Park:

Young Robert Earlston was lucky to survive a fall of 30 feet, after “falling like a rocket” at Glen Park. He was taken to San Francisco City and County Hospital, and was able to walk home later that day. From the San Francisco Call, September 18, 1899. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

“… he had cut loose from a balloon at Glen Park, and went down like a rocket, a distance of thirty feet, striking upon his head on a pile of loose dirt and rocks. A thousand spectators witnessed the thrilling sight.

“Earlston went up a distance of 1000 feet with the balloon. When he left the ground he had hold with his teeth of a rope attached to the bar of the parachute. He at once set to work to give an exhibition of his skill and performed a number of tricks in midair. At the height of about 1000 feet he cut loose. The parachute opened promptly and he began to journey downward, holding on to the parachute bar. As he came down, not any faster than usual, the bar of the parachute struck against one of the new Mission street road’s trolley wires. That threw the aeronaut.”

Fortunately for Earlston, he was able to walk home from the City and County Hospital later that day with only a mild concussion.

At least one aeronaut died after losing control during their descent by parachute at Glen Park. Albert McPherson’s parachute became caught in overhanging wires on the trolley line and he slammed into the trestle bridge. Novice aeronaut Daniel Maloney, 21 years old and a groundskeeper for the zoo and park, nearly met a similar fate in only his fourth flight in front of 4000 people at Glen Park. “When forty feet in the air the young aeronaut lost his grip on the parachute bar and to the horror of the crowd, punctured by the shrieks of women, fell to the ground within a few feet of the point of departure.” He was taken to St. Luke’s Hospital for care. The previous week, his life had been spared when his balloon had caught fire in midair and, when he cut loose, the parachute had still been able to open despite not having reached an adequate altitude. Maloney would go on to make aviation history in high-altitude flight of a fixed-wing craft in 1905 as a “test pilot” for Professor John J. Montgomery of Santa Clara College.

High-wire and other Elevated Acts

Wallenda-like performances were another big attraction at the Mission Park and Zoo, advertised as “… hair-raising blood-stirring events.”

On Opening Day in October 1898, it was reported that high-wire athlete Professor J. Williams, known by many as John Williams, the “Intrepid Cliff House Bird Man,” would attempt a “dangerous undertaking” and “cross over the canyon 1000 feet in width on a tight wire 300 feet above the ground. The performance, if successful, will probably eclipse anything of a like character ever before attempted.” This was an act of true daring for a man who was a mainstay at the Cliff House and Ocean Beach with his trained canaries, parakeets, and love birds, having apparently been challenged to make the crossing for a wager of $500. “Several thousand people” were in attendance to witness his “perilous walk.” Beginning at 2 p.m., it took him 20 minutes to make the crossing.

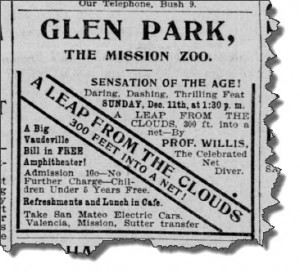

The so-called Bird Man of Ocean Beach and Cliff House fame (which would imply Professor Williams and not Willis) decided to experience the thrill of flying like a bird at the Mission Zoo in Glen Park. From the San Francisco Call, December 9, 1898. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

A Professor Willis (though the media reported that some recognized him as the “canary bird man of the ocean beach,” so this was likely John Williams) performed a “dashing, daring and thrilling feat” in his attempt to dive 300 feet into a net. The act was described as “a human bomb from a clear sky, personified by the world’s greatest atmospheric performer.” Some doubters measured the wire’s height at just under 84 feet, not including the net stretched out 12 feet above the ground on a frame of stilts.

He preceded his dive in late December 1898 with a walk along the tightrope stretched across what he called the “Rockydike Gulch.” Then,

” … a blast of trumpets tore holes in the air of the glen and an impresario told the people that the great show was to begin. By a rope running through a pulley fastened to the wire above, “Canary Birds” was hoisted skyward. Sitting on the trapeze he slowly reached his altitudinal limit, the small boys below yelling all the time about frigid nether extremities. The great dropper was pretty high up and there was only one way to come down, so he hung from the trapeze and dropped. With bated breath and stiffened hair the crowd watched his mighty and successful fall, and then a cheer went up which shook the sky a few feet above the wire and the crowd dispersed.”

In a separate feat, Professor Ramous, “champion high diver of the world,” also known as the “Hawaiian human flying fish,” would, “… attempt to dive into a stream in Glen Park from a pedestal 100 feet in height.” Historically, Islais Creek was the largest body of water in San Francisco and was much wider and deeper before being channeled into a culvert near today’s Glen Canyon Recreation Center. No reports were found as to the outcome of the Professor’s attempt, or if he attempted the plunge at all.

Another act performed by H.C. Romaine was advertised as, “A daring cyclist who rides his wheel down a ladder 160 feet long from an elevation of 100 feet …” as a feature of one week’s “open-air entertainment.” His attempt was reported to be successful.

Entertainers and Vaudeville Performers

A large number of performers, many of them nationally and internationally famous, performed before the crowds at the Mission Park and Zoo. What follows is a short list of advertised shows.

The Australian born riders, George (1890-1955) and Elsie St Leon (1884-1976) with their horses, New York ca. 1915 (ringmistress and clown are unidentified). The act, called Bostock’s Riding School, was presented at fairs and in vaudeville programs throughout the United States into the 1920s. Image courtesy of Dr Mark St Leon, Sydney, Australia. (click image to enlarge)

Studio portrait of Elsie St Leon, Australian-born equestrienne and third generation of the Australia’s St Leon circus family, New York, ca. 1908. Elsie was acknowledged as one of America’s finest equestriennes, the only woman capable of turning an “‘unattended’ somersault on the back of a moving horse.” Image courtesy of Dr Mark St Leon, Sydney, Australia. (click image to enlarge)

Elsie St Leon (1884-1976): A third-generation member of Australia’s most prominent circus family, The St Leon’s, Elsie’s training as an acrobat, equestrian, and all-around circus performer began early. She made her first public appearance in a novelty juggling act at the age of 7. By 1896, Elsie, her siblings, and parents had made their way to North America, often performing as The Five St Leons.

Elsie was only 15 years old when her performance at the Mission Zoo was described as an act of “Clever Horsemanship … performing amazing equestrian tricks.” She apparently had previously experienced equine control issues when it was reported in the Call that her, “… equestrian fetes … will be more wonderful than any of her previous performances. She now has her pony ‘Swipes’ perfectly under control and the tricks she is performing on him daily are phenomenal.” She also sometimes performed on the trapeze. On June 11, 1899, she received top billing at Glen Park as “The Celebrated Bareback Circus Rider in New and Daring Equestrian Feats.” Her performances of bareback riding and hurdle-jumping were apparently well received, so much so that she returned again and again to the Mission Zoo in 1899. The Five St Leons also gave an acrobatic performance at least once at Glen Park. (Read more about the St Leons at pennygaff.com.au)

“Madame Schell in a cage with two lions.” Circa 1910. Image courtesy of the Elizabeth West Postcard Collection, 1887-1955, Harvard University. (click image to enlarge)

Madame Schell and Her Trained Lions: According to advertisements, “Famous lion tamer Madame Schell, one of the successful lion tamers of modern times and the daring of this little woman and the performance of her three ferocious lions excels anything of a like character ever before exhibited in public.” Unlike Elsie St Leon, Madame Schell was not a frequent performer at Glen Park.

Lillian Smith, the “California huntress” of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and archrival of Annie Oakley (ca. 1888). Image courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming. (Click image to enlarge)

Lillian Smith, “The champion rifle-shot of the world”: Lillian Smith was born in 1871 in Coleville, California. She first performed her marksmanship in San Francisco at the age of 10, and by the time she was 15 she was traveling with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show performing as the “champion California huntress.” Lillian and Annie Oakley detested each other, causing Oakley to leave Buffalo Bill’s show after performances in London in 1887.

Other entertainers at the Mission Zoo included, but certainly are not limited to:

Dubell – “celebrated aerialist”

The Troy Trio – “world famous fire kings, direct from New York”

Idaline – “the famous Parisian dancer in her initial bow to American audiences, considered to be the ‘terpsichorean premier'”

Lajess – “double contortion performance”

Edward Olcott – “clown contortionist”

Little Rosie Bennet – “the child wonder”

Kecko – “the gymnastic ape”

Waldo and Elliott– “on the double trapeze”

Al Hazard – “the celebrated ventriloquist”

M. Fletcher and Daughter Edith – “the comedians”

Arnaldo– “feats of hand balancing”

Japanese Wire Walking was one of the many feats performed by the Oura’a Royal Japanese Troupe of Gymnasts at Glen Park. From the San Francisco Call, April 29, 1900. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

The Sawyer Sisters – song and dance artists

Morris Brothers – “feats of strength”

Oura’s Royal Japanese Troupe of Gymnasts– “Japanese wire walking” and other acrobatics

The Schaidelles – “stilt tumbling”

Barney Reynolds – comedy

Baby Troy – female impersonations

Other advertised acts by performers who remained anonymous included a: balancing ladder act, a performance by “educated cockatoos,” bareback trick riding, dramatic reading, black-faced comedy, mind reading, triple horizontal bar work, acrobatic tumbling, and “other feats of merit.”

Musical Performances

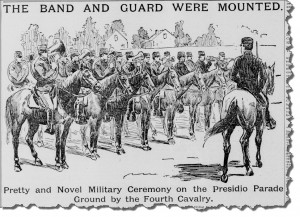

The Fourth Cavalry Band – The U.S. Army transferred the headquarters of the Fourth Cavalry and its band from Fort Walla Walla, Washington to the Presidio in June 1898. At the time, they were only one of four remaining regiments in the U.S. Army who still performed as a mounted band. The Call reported that,

“With the exception of the cornets, all the brass instruments of the bandsmen

The Fourth Cavalry Band, one of only four remaining mounted bands in the U.S. Army in 1898, had just transferred their headquarters to the Presidio in San Francisco and quickly became popular among the Glen Park pleasure-seekers. From the San Francisco Call, June 1898. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

encircle the shoulders, enabling them to hold them steadily and firmly when walking, trotting, or even galloping. Even the horses were noted to enjoy the music and seemed to march in step.” Led by a Colonel Morris, the Fourth Cavalry Band would perform several times in Glen Park, including on Opening Day in 1898.

The Tivoli Theatre Orchestra was also noted to have “rendered some choice musical selections.” Other concerts by the Glen Park Band and the Warren Lombardero Mandolin and Guitar Orchestra also regularly performed.

Events

A Flag Day parade, and foot races for boys and girls were part of the festivities of May Day, 1900. From the San Francisco Call, May 2, 1900. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

Some weeks at the Mission Zoo, it was the pleasure-seekers themselves who put on the show. As announced one week in the Call,

“The games are to be one of the most interesting features of the afternoon. There are all kinds of races, and races scheduled for all kinds of people. Age or weight will be no bar, nor will sex or social condition. There will be races for girls and for boys; for young women and young men; for married women and married men; for fat women and fat men. Then there will be three-legged races, egg races and bicycle races. There will be an amateur race for the Labor day medal, a cross-country bicycle race for the Glen Park cup, a fine hose coupling contest by members of the Fire Department, a tug-of-war between members of the different unions and a cakewalk.”

Cake-walking, the big fad of the late 1890s, was originally developed by enslaved African Americans in the South to mock the stiff, waltzing dance of their white owners. White Americans eventually developed black-faced minstrel shows to mock this African American dance, not realizing the joke was actually on them. Dances were judged and the winners often received a piece of cake. Cakewalking is considered to be the root of American jazz music (Learn more about cake-walking).

The German-American League held a celebration in Glen Park in 1903, one of many local clubs to rent the grounds of the Gum Tree Tract for picnics and parties. Bowling was a popular game, as was dancing under the stars. It is not clear what activity is being performed on the left side of this image. From the San Francisco Call, October 5, 1903. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

Bowling: Often, private clubs would schedule picnics in Glen Park. The German-American League had one such picnic and included bowling as part of festivities that continued well into the night:

“The whole German colony of the city, with their lunch baskets and their flaxen haired children, flocked out to the warm little glade in the Mission hills before the sun was four hours old, and there on the sun-browned hills and in the shaded glens reveled to their hearts’ content until the moon shone over Twin Peaks.”

Homing pigeon races: Homing pigeons were often released from Glen Park to make their way back to home base in East Oakland. From the number of articles in the news media around the turn of the 20th century, homing pigeon races up and down the Pacific Coast were a big event. Birds were rated for distance and time, and champion birds could cover almost 900 yards per minute and fly nearly 400 miles without stopping.

While most racing homing pigeons were identified by a series of letter and numbers, one bird seemed to fly above the rest. Skyrocket, shown here, could cover 400 miles in a little over 13 hours. It is not known if Skyrocket ever raced at Glen Park. From the San Francisco Call, May 25, 1899. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

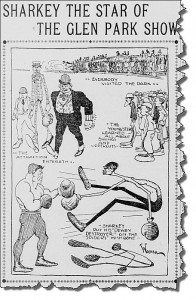

Boxing: In June of 1899, a “scientific sparring exhibition” was scheduled between Tom Sharkey, a self-proclaimed “Champion of the World” and Spider Kelly, a former sailor. The match was to be refereed by Joe Kennedy. It was noted that the fight would occur during the daytime so that “variascope” pictures could be taken, and was staged to help promote and attract big professional fights to Glen Park in the future. As reported in the Call,

“… several thousand people swarmed out over the hills to the scene of the promised exhibition. Many of them had never had the honor of gazing at the muscular form of the pugilistic wonder and they were determined not to overlook the present opportunity. The exodus from the city commenced about noon and for the next four hours the electric cars on the San Mateo line were taxed to their utmost capacity. Passengers clung to the sides and rear and even clambered upon the roofs of the cars, and when driven from the latter hung by their hands to the sign that ran along its edge. Others clung to the window frames and to one another until there was nothing left to cling to. Occasionally a passenger lost his grip and went rolling and tumbling along the road, but, although several of the victims received severe shakings up, they invariably refused to give up the trip and retire for repairs …

The big event at Glen Park in the summer of 1899 was the mismatched bout between professional pugilist Tom Sharkey and ex-sailor Spider Kelly. The event was actually a promotion to attract future professional fights to Glen Park, so there was no real victor in this bout. From the San Francisco Call, June 19, 1899. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

“Sharkey looked big enough to swallow his shadowy opponent, but Kelly ducked and sidestepped in the most approved fashion and the blows aimed at his head usually went wide. ‘Dewey’s Destroyer,’ as Sharkey has rechristened his good right arm, was not brought into action to any great extent, and to that fact the Spider probably owes possession of an undamaged anatomy. The sailor was as live as a cricket, however, and although Kelly was suffering from a severe case of indisposition the exhibition was eminently satisfactory and met with the unqualified approval of the audience.”

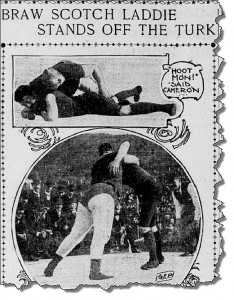

Wrestling: Crowds also made their way to Glen Park to view Hali Adali, better known as “The Terrible Turk” or “The Sultan’s Lion,” wrestle J. J. Cameron, “a Bonny Scot.” The more hulking Adali was expected to win the contest within a matter of minutes, but,

Hali Adali and J.J. Cameron in a wrestling bout at Glen Park, May 1900. When Adali grabbed the Scot’s so-called “kilts,” Cameron “hooted” so loud that Adali released his grip. From the San Francisco Call, May 7, 1900. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

“The Scotchman wriggled and twisted, dodged and sweated to such good purpose that the Turk was unable to throw him. Whereat the populace was glad and cheered loudly. The ‘Terrible Turk’ put forth his best efforts, but Cameron’s accent was too much for him. When Hali Adali secured his famous ‘jail’ hold the braw Scotchman ejaculated, ‘Dinna ye ken, mon, ye canna doon me,’ and when the Turk caught hold of the Caledonian’s kilts he howled ‘Hoot mon!’ so lustily that the ‘lion’ released his grip.”

Automobile: A modern marvel before the turn of the 20th century, an automobile was advertised to be “in operation” at Glen Park one Sunday in September 1899, and was to “convey passengers around the park.”

Electricity: The power of electric light was still a novelty on July 2, 1899, when Glen Park was reported to be “aglow” with incandescent and arc lights, after the grounds were “extensively wired.”

Military Games

Mounted broad-sword contest: This exciting event was scheduled more than once and was not onlyperformed by two of the most “scientific sword fighters in the country,” but also on horseback. One contest featured a mounted sword match between Sergeant G.W. Moffitt of the Fourth Cavalry (U.S. Army, Presidio of San Francisco) and Lieutenant J. L. Waller of the National Guard. Both were noted to be “deft and handy with their weapons” and spectators were promised an exciting exhibition. Even though Sergeant Moffatt “broke his sword during the third attack, he won the contest with the close score of 11 to 9.”

Shooting Range: As noted in Part III, a shooting range had been constructed so that shots could be fired from one side of Glen Canyon to the other. Military batteries from around the Bay Area would venture to Glen Park for a weekend stay. It was often reported that the soldiers had enjoyed the grounds with an elaborate dinner and party the previous evening before competing against each other the next day.

Unbeknownst to modern pleasure-seekers, sham military battles took place in the wilds of Glen Canyon a century ago, helping members of the California National Guard hone their skills in practice battles that included real weapons. This sham battle took place in Glen Canyon 12 days before the Great Earthquake. From the San Francisco Call, April 6, 1906. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. (click image to enlarge)

Sham Battle: Practicing battle tactics and maneuvers with actual weapons was a new requirement for the U.S. Army in 1906, and Glen Canyon was the perfect location for local National Guard units to receive their hands-on experience:

“Company F. N. G. C. held a military field day at Glen Park yesterday. One of the features was a sham battle which was realistically presented by the enthusiastic militiamen. The ‘battle’ was waged with all the picturesque effects of the ‘real thing.’ Captain Stindt led the center in the charge of Company F against an invisible enemy. Lieutenant Hyde led the right and First Sergeant Bush the left.

“Taking advantage of all cover as they would have done had they been charging a real enemy with long range Mausers, the company crept up the slope of a hill until they were within fifty yards of the point to be taken. Then with a yell the company sprang from cover and rushed up the slope with fixed bayonets and charged the imaginary earthworks.

“After the ‘battle’ was over a number of the sports which are part of the day’s work with the regular army men were taken up, including cartridge and bayonet races. Target shooting wound up the day’s outing.”

The Final Measure of Success

Bears, elk, a big baboon, and a lonesome seal. Rocket birds and vagrant ostriches. Human bombs and atmospheric performances. Women with lions, women with guns, acrobatic women on the backs of horses. Pugilistic bouts, sham military battles, military bands on horses marching in step. The variety and inherent danger of many of the acts presented at the Mission Zoo and Park almost 115 years ago appears to have succeeded in bringing the masses to Glen Park.

But did it succeed in selling home lots? After all, that was the plan concocted by Baldwin & Howell: start a zoo to give people a good enough reason to make the journey to the the City’s Outside Lands at Glen Park. The next post of this series, Part V of The San Francisco Mission Zoo: The Wilder Days of Glen Park, will attempt to answer that question.

[This article was updated on June 30, 2018 to add new information about Daniel Maloney]

Sources

-

- Lockwood, C and Craig ,C. Woodward’s Gardens, c. 1860. Available at Foundsf.org.

- San Francisco Chronicle, various issues, available at San Francisco Public Library Articles and Databases.

- San Francisco Call, various issues, available at California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- San Francisco Examiner, various issues, available at the San Francisco Public Library.

- Oakland Tribune, various issues, available at NewspaperArchive.com.

- History and Culture, Wright Brothers National Memorial. Available at the National Park Service.

- Anonymous. Thomas Scott Baldwin. Parachute Jump, 1887. Available at the Cliff House Project.

- Recks, R. Baldwin, Thomas A. Available at Who’s Who of Ballooning.

- Freeman, J. Johnnie the Birdman: The Original Birdman of San Francisco. Available at Outsidelands.org.

- San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. LID Basin Analysis Technical Memorandum Islais Creek Drainage Basin April 2009. Available at the SFPUC.

- St Leon, M. Personal communication, August 2012. St Leon family history available at pennygaff.com.au.

- The American Experience. Lillian Smith-Biography. Available at PBS.org.

- Brightwell, E. The roots of jazz – cakewalk – Amoeba’s jazz week. Available at Amoeblog.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update September 3, 2012.

Marion

/ August 26, 2012Elk were mentioned at least 2 times in this article. I wonder why “Elk” street got it’s name? I especially like the part about Annie Oakley’s rival Lillian Smith. With all the animals and dare devil activity it makes the Folsom Street fair seem tame 🙂 Great article, the most entertaining thus far.

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ August 28, 2012Thanks for your comment, Marion! I think it’s very likely that the name “Elk” is a remnant of the zoo. In the image of Admission Day at the top of Part IV of The Mission Zoo, there is a path coming down the hill that is the route of today’s Elk Street. Perhaps further research will tell.

Frances

/ March 31, 2016I was told by an older resident of Glen Park that he had cages and

also a bear pit in his back yard on Congo Street. Was that part of the zoo?

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ April 2, 2016Frances, Thank you so much for your information! I have been told that the “zookeeper” for the animals in Glen Park lived on Congo. I will contact you offline to find out more details. Many thanks — Evelyn