After a brief hiatus, Tramps of San Francisco is back on track, searching for evidence of the City’s forgotten histories! After unearthing the story of the proposed Mission Park and Zoological Gardens, along with three months of weekly research and posting of new topics in what was supposed to be a leisurely hobby, it was time to sit back and revisit the concept of moderation. It became apparent that in order to remain sustainable, greater balance between Tramps and other activities is required.

Thanks to those who have shown your support during Tramps’ respite, as well as those new Trampers who signed up for email notifications and registered Likes and Follows during the downtime. Virtual treks in search of San Francisco’s forgotten histories are returning, but will now occur with less frequency than weekly.

Given that, embarking on long tramps and extended excursions to discover our local history is not necessarily a requirement. Sometimes, clues may be found in locations as close as our own backyard. This was my eye-opening discovery when I recently began to prepare our backyard for new sod.

I received my bachelor’s degree in anthropology more years ago than I’d like to recall. Then, a few years after moving to San Francisco, I participated in the initial phases of an archaeological dig at a Miwok shell mound on Strawberry Point in Marin County. After all these years, the urge to lay out a grid and dive head first into dirt with a trowel, whisk, and dental pick has never really left me.

We moved to the Glen Park district several years ago. Unfortunately, the previous owner of 20 years did not disclose any details about the history of the lot or structure, so I’ve always been curious about what might lie beneath.

We had our first chance at a peek a few years ago after removing a diseased 50-year old Monterey pine tree. All we found, however, was an extensive root system. We eventually expanded an existing patio throughout much of the yard, and added a raised planting area in the middle to cover the partially ground stump. This left only the perimeter of the yard available for future digging and planting.

The rear retaining wall, approximately 10 feet high. It appears to be made of an old type of concrete composite, with slots for beams, and some remnants of wood beams. Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

Our backyard is small and can only be accessed by ascending eight steps to reach the top of a 5-1/2 foot retaining wall. Once in the yard, one is faced with a 10-foot high retaining wall at the rear that is constructed with an old composite-like concrete. The wall ends abruptly at the southern border of the property, and to the north it is replaced by an old wall made of small blocks of rock and concrete. About 7 feet above ground, our concrete retaining wall has slots for what might have been used for beams. They are spaced about one foot apart, and a few have vestiges of old wood. In the middle, a single buttress protrudes from the wall into the ground. There is also a remnant of a masonry wall on the south side. It is an earthy red and has evidence of an embossed floral pattern. Finally, along our north boundary rests a two-foot high wall made of what appears to be a very old form of masonry, with a small keystone positioned in the middle.

These structures have been a mystery to us since the day we moved in. Clearly, something was constructed here a very long time ago. But, what was it?

The north wall is about two feet high, is comprised of an early form of masonry, and had a keystone in the middle (just to the left of the shadow of the tree trunk and post). Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

Researching the history of our lot has led us to some surprising revelations. While our house was built in the mid-1920s, a previous owner had moved our structure to today’s address in the Fall of 1959. After some investigation, we believe that our structure’s original location abutted the automotive divide known as the Bernal Cut between the Bernal Heights and Glen Park districts. A little more digging and we surmised the move may have been the result of the conversion of San Jose Avenue in the Cut from a more peaceful two-lane road and railway into what may have been anticipated to become a polluted and blustery four-lane shortcut to a major freeway.

While former Governor Pat Brown and others believed that progress meant snaking a series of freeways back and forth, up and down, and over and under the City of San Francisco, the neighborhoods about to be bisected didn’t agree. In Glen Park, the San Francisco Freeway Revolt was spearheaded by a group of women who became known as the Gum Tree Ladies. Their gumption and determination helped guide the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to vote down seven of nine freeways throughout the City in January, 1959. This stopped dead in its tracks a plan for a major route right through Glen Canyon that would have bored under Twin Peaks and Mount Sutro. Initially proposed as the Circumferential Expressway (and later renamed the Crosstown Freeway), it would have emerged at the southeastern edge of Golden Gate Park before galumphing its way to the Golden Gate Bridge.

Section of block with an embossed floral design. The perimeter of the image is in black and white, in order to highlight the embossing in the center with actual color . Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

While we don’t know for certain, it’s possible our house may have been peripherally connected to a major and important early environmental grassroots movement in San Francisco. Once victory was achieved, the previous owner may have desired refuge from the increasing noise and pollution of an already expanded San Jose Avenue, literally picked up the house and moved it almost a mile. It must have been some sight to see the house crawling up a hill!

Next, we discovered papers at the San Francisco Water Department documenting a request for a water hook-up on our lot about one month after the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. This may help explain an old, rusted water pipe sticking out of the masonry wall on the north side of our property. In earlier landscaping activities, we had found a knob from an old gas stove and a small, white porcelain insulator used in early 20th century electrical systems. These all represented to us tangible evidence of our lot’s first tenant.

One month after the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, a carpenter from Canada applied for a water hook-up. This old water pipe coming through the wall may be a evidence. Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

Research of census records found that the gentleman was originally from Canada and worked as a carpenter, a much-needed trade during the years of reconstruction following the Earthquake. I’ve misplaced an additional document but I recall it stated he was living in nothing more than a shack in 1930. His death certificate indicates he was still living on this lot at the time of his passing in 1932, a demise described as traumatic and requiring an inquest. Whether any conclusions were reached by the medical examiner requires additional research.

But, was the carpenter the very first tenant on our lot? Now that we know our neighborhood was included as part of the lands of the Mission Park and Zoo, I’m viewing the rear retaining wall and the short wall on the north side of our backyard from an entirely new perspective. Are these structural remnants evidence of the carpenter’s shack? Were they outbuildings of one of the Rock Gulch (an early name for Glen Canyon) dairies established in the 1870s? Or, could they be remnants of structures built by Mission Zoo management during the zoo’s heyday in 1898 and 1899?

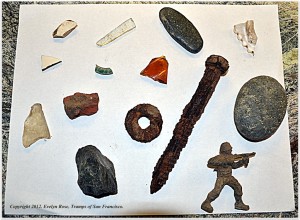

As I recently prepped the yard for the laying of sod, I turned the soil with a shovel. Holding my leaf rake parallel to the ground, I sifted the dirt and filtered plant material for composting. As a happenstance, other buried objects were revealed. I unearthed a variety of intriguing artifacts, including two types of white porcelain fragments, shards of clear glass (one with scalloping on the edge), brown glass, and a thick (1/4″) piece of translucent glass. In addition, I found a 1960s-era plastic toy soldier, a small, curved piece of a white and green milk glass, two small river-worn rocks, a piece of old brick, a nice piece of greenish-black serpentine (with a silky, obsidian-like feel), and an old and very rusty 5-1/2″ long, 1/2″ thick hex bolt with a 1-1/2″ washer.

While the hex bolt was impressive, the surprise find was along the southern edge of the yard, 5″ down in the rich Glen Park soil. My shovel scraped along what I first thought was a rock but, upon closer inspection, it was something far better. I quickly grabbed my trowel and whisk, got close down in the dirt, and soon unveiled a concrete pedestal measuring 9″ by 9″, with a raised edge 1-1/2″ wide all around. In the center were three small, rusted spikes that had originally pointed upward but that had since been pounded sideways. It seemed very well made with a fine cement and did not appear to be cheaply constructed, as might have been used to

Artifacts located while gardening include pieces of porcelain, glass, stone, a child’s toy, and a large and very rusted hex bolt and washer. Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

construct a shack.

The next weekend I planned to lay sod on the opposite side of the yard. I was anxious to see if another pedestal was positioned exactly opposite from the first. Unfortunately, I had started later in the day than originally planned. The dirt on the north side was much harder to dig into. After some effort, and with a hefty dose of rain predicted within the hour, I hastened to finish the task at hand: the laying of sod. I would have to leave the archaeological dig for another time.

What appears to be a base for a pedestal was uncovered five inches beneath the soil. Measuring 9 inches by 9 inches, it appears to be made of a fine concrete. Copyright: Evelyn Rose, TrampsofSanFrancisco.com.

After 1932, it would be 27 years before our lot would again be occupied. The assortment of items found in the soil, the buttressed retaining wall, an old masonry wall with a keystone, a remnant of wall with floral embossing, and a finely made cement pedestal all represent intermittent use of our lot for over a century. Whether the structures that remain have any historic value remains to be seen.

In September, 2012, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously approved legislation to simplify and standardize the application process for the Mills Act Program. The Mills Act promotes the preservation of historic landmarks and is considered the greatest economic incentive in California for private property owners of historic buildings. It’s possible these remnants of structures might not qualify for the program, but the carrot that dangles in the form of property tax reduction certainly provides an impetus to continue with our property’s research.

So what’s in your backyard? Become a backyard archaeologist and document your property’s history by:

- Familiarizing yourself with the history of your city, with particular attention to the history of your neighborhood. Identify features of your property that may predate your house, and whether similar features can be found elsewhere in your neighborhood;

- Examine historic resources at your local library, historical societies, and online, including newspaper archives, municipal reports, and old City phone books and directories;

- Review the file of your property’s documents at your local City Hall and utility departments. Learn more about how to research your property from the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board (1992, revised 1993 – while the information provided remains pertinent, addresses and telephone numbers may have changed), available at the San Francisco Public Library;

- Perform genealogical research about your property’s former residents, if known. If unknown, use genealogical records (such as those maintained by Ancestry.com) to help identify former residents of your address;

- Search the Web using key terms specific to your area, using a variety of combinations. You’ll be amazed at what you come up with;

- Multi-task while gardening: refresh the look of your yard and seek historic (and possibly even prehistoric) artifacts;

- Get a shovel, leaf rake, trowel, whisk, and even a dental pick, go out to your backyard, and start digging! Laying out a grid is the preferred method of excavation used by archaeologists. This helps establish the context of a particular artifact in relation to other identified artifacts and the grid site at large. While you may not want to lay out a grid over your entire backyard so that you can maintain easy access, you may want to grid a section of your yard as a science project for young and old alike. The Friends of Bonnechere Parks in Ontario, Canada, provide an easy plan to follow;

- Use your leaf rake to sift material, or construct a shaker screen (see example on Flickr). Keep a record of the location and description of any artifacts you may find. If you locate something that may seem especially noteworthy, contact an expert for more information;

- Several residential areas in San Francisco and other locales were formerly cemeteries. Perhaps some areas where you live were once Native American burial grounds. While such a find may be unlikely on your property, unearthing any evidence of human remains requires you to immediately stop digging and call your local medical examiner or coroner (check the laws of your area for the appropriate action);

- Evaluate your findings and determine whether an application to the Mills Act Program (for residents of California; other states may have similar laws) is warranted.

Sources

- Carlsson C. Revisiting the San Francisco Freeway Revolt. Available at SF.StreetsBlog.org.

- Issel W. “Land values, human values, and the preservation of the City’s treasured appearance”: environmentalism, politics, and the San Francisco Freeway Revolt. Pacific Historical Review. 1999;68:611-646.

- Verplanck CP. Glen Park: The architecture and social history. Available at San Francisco Apartment Association.

- Anonymous. Board of Supervisors votes to expand access to Mills Act Property Tax Relief. Available at San Francisco Architectural Heritage.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update December 2, 2012.

Michael Acker

/ January 31, 2016Exciting article in an impressive blog. I found it Googling “Leavenworth.”

I’m writing the Arcadia book on the Springs area of Sonoma Valley. T.M.Leavenworth lived here after he left SF in 1848, and bought and sold property.

Please also see my website springsmuseum.org.

thanks!

Mike

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ January 31, 2016Dear Mike,

Thanks so much for your comments! I hope Tramps of SF was helpful with some of your research. I was not aware that Leavenworth had ultimately settled in Sonoma! Best of luck with the book, and after taking a look at your website, I look forward to visiting your new museum, once it’s complete! — Evelyn